GM Karsten Mueller shouldn’t need a presentation, he is likely the GM who has written more books about the endgame in chess history! He publishes regularly on Chessbase Magazine a column on chess endgames which is simply fantastic, and big like a book, since he presents something like 50 different endgames every 2 months.

I discovered this book in fact thanks to a Chessbase Magazine which mentioned it, but in German! Then I discovered it existed also in English and I got it immediately, because I do believe whatever GM Mueller writes is definitely valuable, interesting, and can improve my chess.

This book intrigued me, because it shows the idea that there is more to chess than just clicking on the engine button and let the silicon monster find the correct move. Yes, the famous phrase given by Plato in the Phaedro “know thyself…” (probably taken by the inscription at the entrance of the temple of Delphi) is quite general, but chess can be the tool we need to use to know ourselves, from the way we play our games, the openings we use (and here I am repeating what GM Keymer wrote in the preface, a thought I had recurrently for many years) or the risks we take during the game, one can understand us as players.

In the introduction we discover the book is based on an economic theory model presented in another chess book. Yes, this is becoming quite amazing, chess books are showing us that theories developed in other fields, can be applied to the world of chess.

When another book or player is mentioned, I generally try to discover something about them, in order to better understand what an author is trying to convey. In this case I have a huge chess library, and I simply went to find a dusty book published in 2005 by Gambit, and began to read.

Jumping from this book to the Introduction of “Foundation of chess strategy” Lars Bo Hansen mentions one thing I understood from following some of Chessbase DVDs made by GM Mikhalchishin.

In those DVDs Mikhalchishin clearly outlined the minimum knowledge one should have on how to deal with some pawn structures, the Isolated Queen Pawn, the minority attack etc. Lars Bo Hansen points out nowadays this kind of technical knowledge is available to everyone (while before was mainly part of the master level players baggage of knowledge), hence we need to go beyond that in order to win our opponents. In fact there is a very deep phrase in that introduction: “you need to shift focus to how win the position to how defeat your opponent.”

Did I catch your attention? Yes? Then let’s return to this book, because also here in the introduction there is something which made me think deeply. As always one needs to know something about chess history, and of course he needs to have seen the games of some world championship matches. For example the Match Kasparov vs Kramnik, I was lead to believe by Kasparov that Kramnik was the best of the two for opening novelties, in fact I think Kramnik provided many ideas to Kasparov when they were working together. But in the introduction is mentioned: “An example is Kramnik’s victory in the World Championship Match in London 2000 against the activist Kasparov. Kramnik managed to always steer the game in the desired direction, so that Kasparov didn’t even get an opportunity to show what he is able to do in positions with attack and initiative.”

From the above quotation we begin to be introduced to the idea of different types of players, Kasparov is an activist, Karpov is defined as “reflector”, Fischer is a “pragmatic” and Steinitz a “theorist’.

In fact inside this book we find positions which are designed to help us discover who we are, more than discovering what is the right move, a thing many do clicking on an engine, and then magically thinking the engine and them are the same!

I will begin to give a review of the chapters and their content, and if someone is interested then the next step would be to acquire this great book, and begin the journey of chess-self discovery!

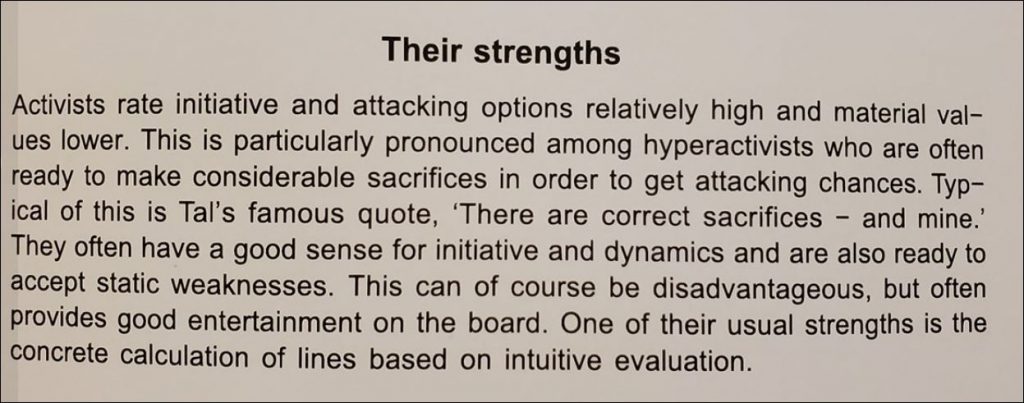

Chapter One is dedicated to describe the “Activist” chess players, their strengths, their weaknesses, and the games and positions they like or dislike to play. It is difficult to review the chapter, because the authors made really a huge work to detail how the “activist” deals with all phases of the game, and they also gave us a set of positions for each phase of the game to test ourselves and see if we think like an activist. More than 60 pages are dedicated to games and exercises to solve.

Here we can read the definition:

This is the list of names of champions who are considered activists: Alekhine, Tal, Spassky, Kasparov, Anand, Shirov, Morozevich, Topalov, Pillsbury, Anderssen, Bronstein, Larsen, Taimanov, Aronian, Judit Polgar, Karsten Mueller.

I tried to make an experiment, and see if through watching some games of these champions I would find such definition accurate. I’d like to share the games I found which seems to fit the label given to these champions, I began with Anderssen and Pillsbury:

After watching some of Anderssen’s games one can feel the guy is really dangerous when he has the bishop pair. Hence if I’d play Anderseen I would try to find an opening where the bishops are exchanged. I also felt the human spirit winning upon materialism. Anderssen didn’t care about losing material, he cared about giving checkmate! We can also notice the difference between Anderssen’s games, mostly played with 1.e4, and Pillsbury which are against top opposition, often Lasker, and with 1.d4.

Alekhine also has some interesting games. Here one I found which I believe could fit the definition given to this great world champion:

Obviously I don’t want to take away the pleasure of researching more games for the reader of this article, and if one buys the book, he can understand more also about the weaknesses of such great players, and put them in the context of the games watched. Today there are a lot of great resources one can use for searching games, like Megabase 2021,

or always made by Chessbase a DVD for each of the World champions which also has a complete database of all their games.

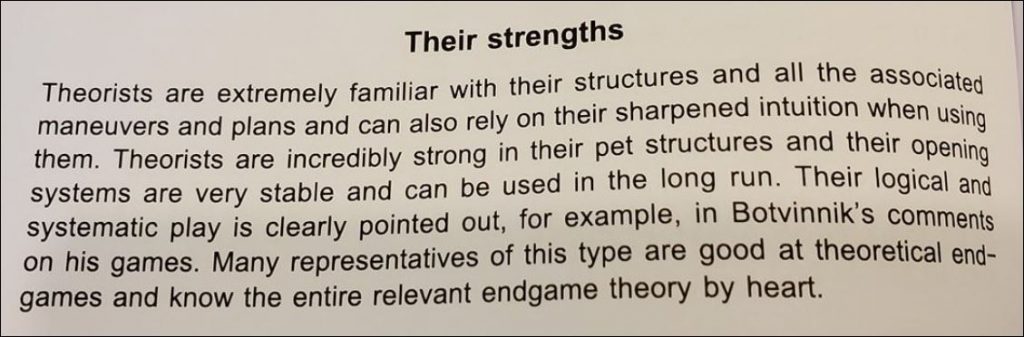

The next three chapters, as we have seen in chapter one, are dedicated to describe, and discover: Theorists, Reflectors, and Pragmatics. As for Chapter One there is in each chapter a wealth of games used as examples, and of course positions we need to put on a board, and think through and through.

Chapter Two:

This is the definition given to theorists in this chapter:

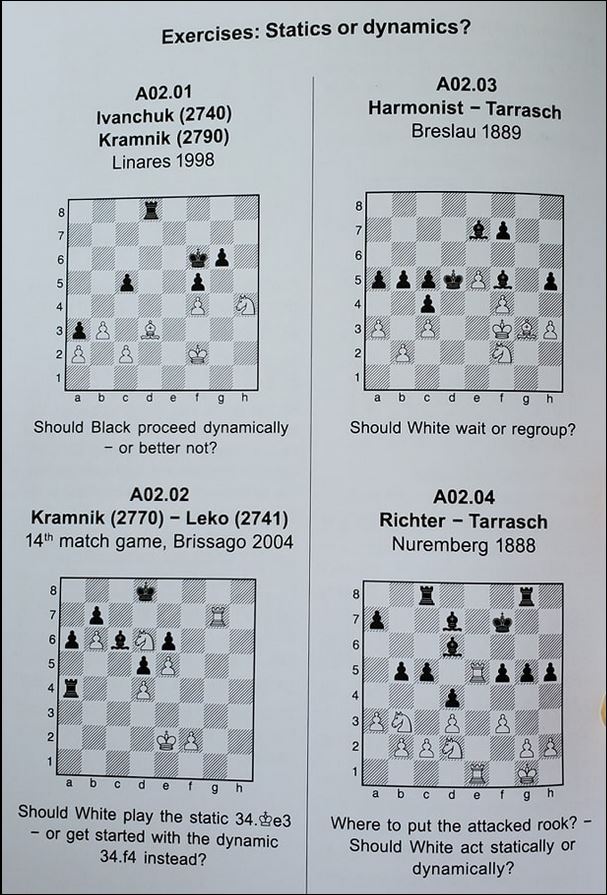

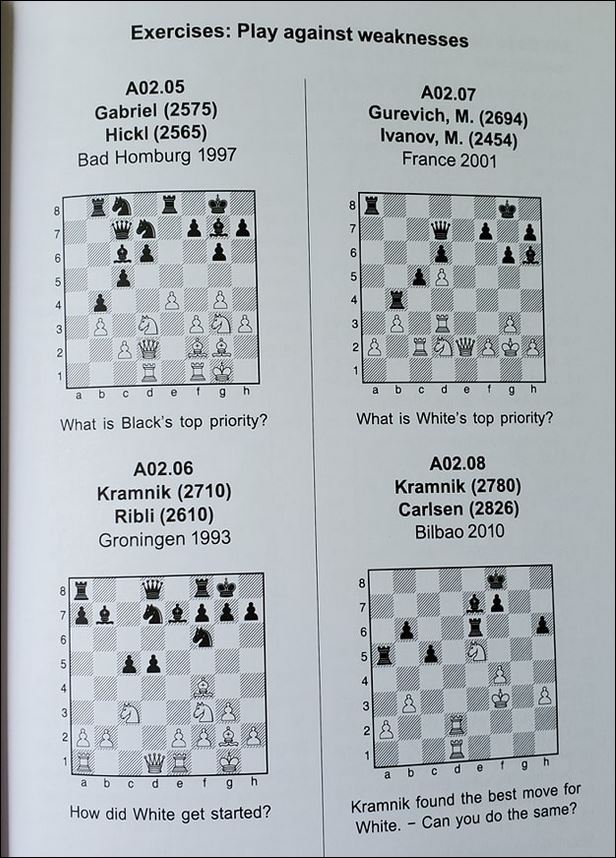

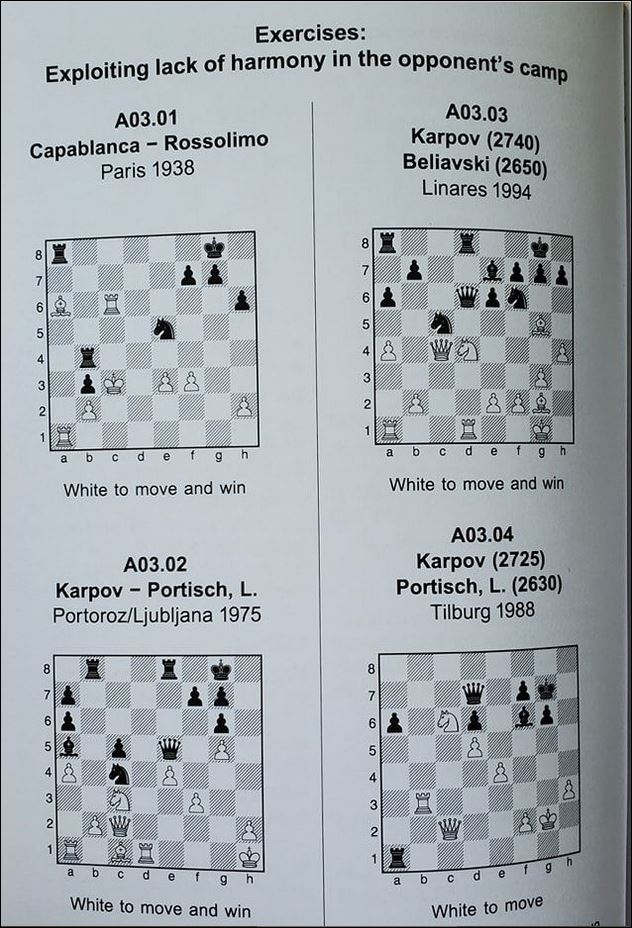

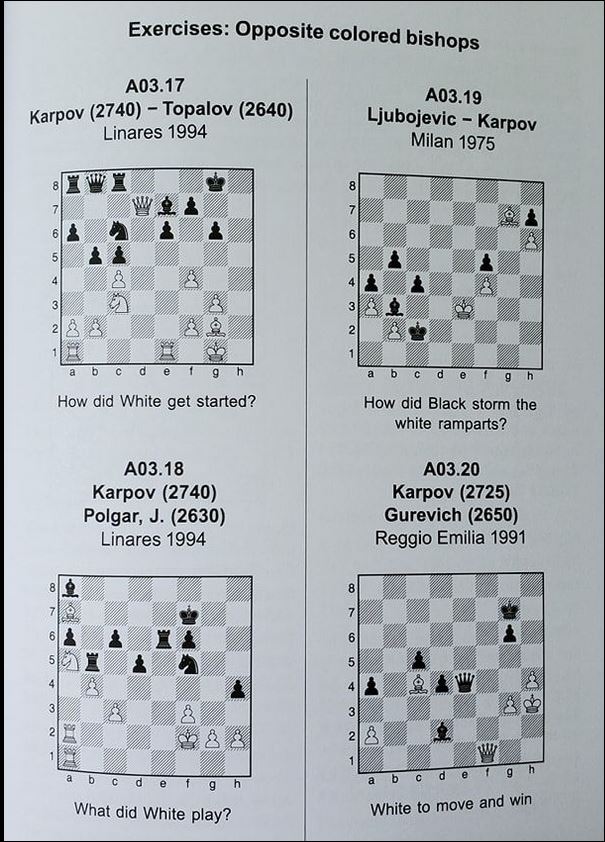

Now I’d like to continue the review of the book showing some images, which in turn point at the exercises we can find inside the book. Yes, the online tactics trainers while good to obtain knowledge of typical patterns, don’t really cover what happens in our games. Often we need to take decisions, and find candidate moves, in positions which don’t have tactical elements. Hence it’s important a workout like the one proposed in this book to improve our chess.

Maybe the reader is not convinced of what I wrote above, let me show you again, since one image is worth 10000 words, the authors of the book did their homework, and found different positions to drill us, and show us what a theorist is!

This is the list of the champions who are considered theorists by the authors: Tarrasch, Nimzowitsch, Leko, Giri, Meier, Ulf Andersson, Sedlak, Tiviakov (famous for his Scandinavian Qd6), Ponomariov, Berliner (a correspondence world champion, when there were no engines to rely upon!), Moskalenko (famous for his opening books on the French, Dutch, Budapest gambit etc.), Mark Dvoretsky (the trainer par excellence!), Dorfman (famous for his chess method), Bangiev (also known for his squares strategy) Lars Bo Hansen.

Chapter Three:

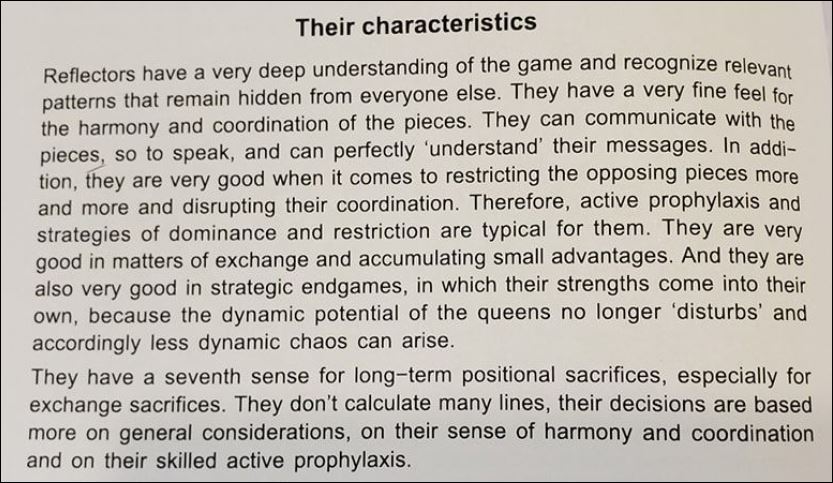

Here the definition:

Please keep in mind I cannot give all the book’s content, the authors did a more profound work on defining these chess personalities showing their weaknesses and other traits which one can get only through buying the book. The authors also proved their points through a holistic work which includes all the phases of the game, and for which they provided games, or positions and then exercises.

Notice how the authors also looked into how these champions use some pieces, and through a page of exercise, but there are many, ask us questions which make us understand how deep the game of chess can be.

One could be curious and wanting to know which champions were selected by the authors which fit the definition, here the list: Capablanca, Smyslov, Petrosian, Karpov, Carlsen, Adams, Rubinstein, Keymer, Bischoff.

The authors included Alphazero and LeelaZero, but I cannot agree with such choice for a simple reason: engines are not humans, they do whatever the programmers tell them to do. I will make an example: after one year that LeelaZero was available, I played a match with Hiarcs running on my mini Ipad, against LeelzaZero. Often the games would finish in a dead draw endgame which even a 1000 rated player would understand it’s a draw. LeelaZero hailed as AI, couldn’t even understand that, and played the endgame till the end likeI’ve seen every engine to do up to now, yes like those engines which are not labeled as smart.

Chapter Four:

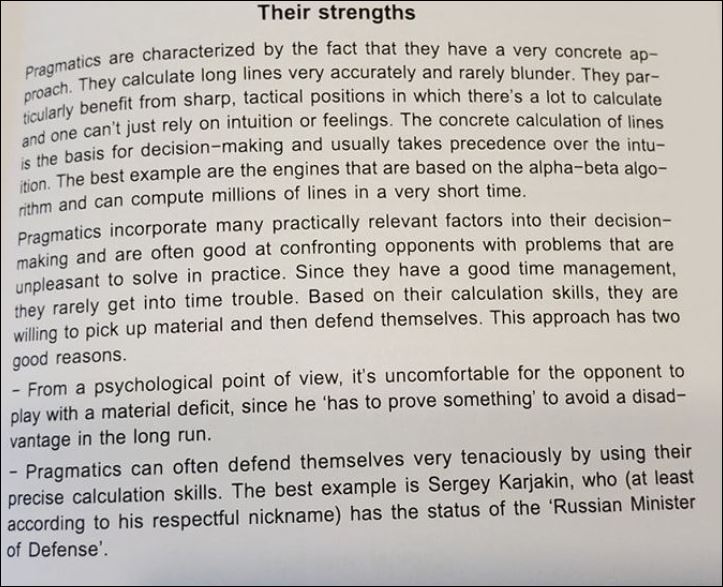

We begin with the definition:

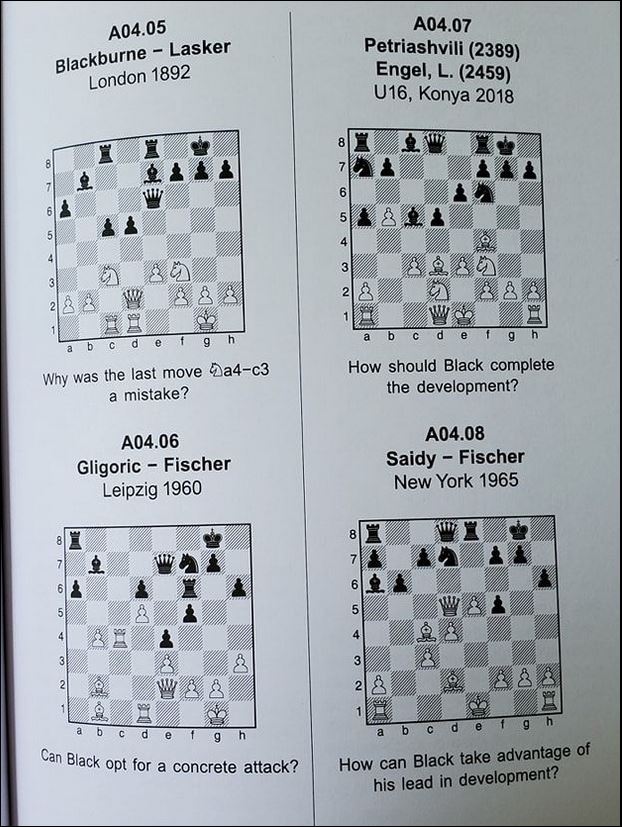

And then show one of the pages of exercises, which come after the authors explained clearly what a pragmatic is with games and fragments. This is an example of the questions asked:

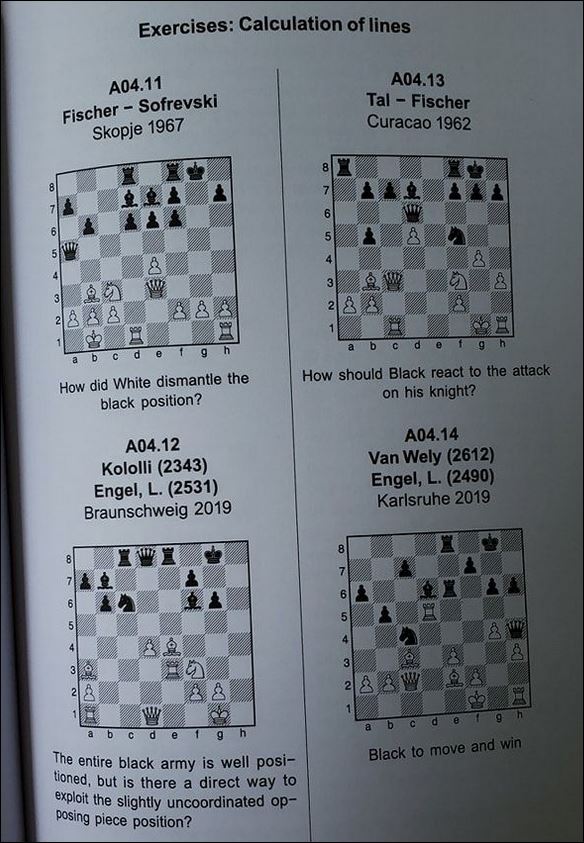

As mentioned before the authors delved deeply into the characteristics of each personality, in this case they show how good are the pragmatics to calculate, and offer the readers the chance to see how good they are to match such calculation power:

Obviously I don’t want to spoil the end of the book with the list of champions who are considered Pragmatists, the reader will have to buy the book to discover them!

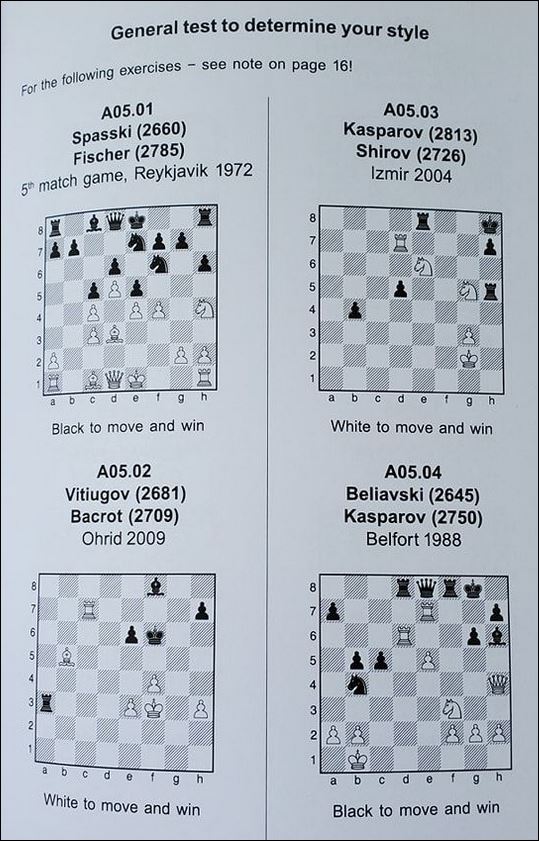

The book ends with a series of tests to discover which type of player one is.

Pro and Con:

Opening the book I found a nice bookmark with the site of the publisher. This is something more publishers should provide with their books, because it helps when one stops reading, and closes the book.

The book is not small enough to be kept in one’s own pockets, so I suggest to buy 2 copies, and cut all the diagrams of one book, make some flashcards, so one can bring them around when commuting to go to work, or any other trip. In this way we can try to memorize the ideas behind the position.

Final Thoughts: I like this book because it is a journey of chess self-discovery! Yes, we all want to improve, but what if improvement needs to pass through discovery of who we are? What if the rating we have achieved is not based only on the knowledge of openings, tactics and endgames, but upon our lack of knowledge of who we are, and in order to achieve the next step in this journey to mastery we need to actually know who we are, and adapt that knowledge to our play in tournaments? Our times due to the huge amount of information we have at our fingertips have changed many human endeavors and made definitely more difficult and competitive the same achievements one could have achieved 40-50 years ago. I see many adults and senior players complaining when they have to play kids, because the kids outplay them in some chess areas… but thanks to reading this book, they could outplay their younger opponents like Kramnik did for Kasparov.

Pingback: The 4 players type standard model… a review! - Chess News And Views