In my first article I described that chess does not only consist of openings, tactics and tournaments, but that the chess enthusiast can and should also show an interest in the history of the game and the playing material. This recent article shows the close links between the two.

Today I want to tie in with the topic of chess collecting. I will give a brief historical outline of how chess pieces have changed over time.

The origins of the game of chess

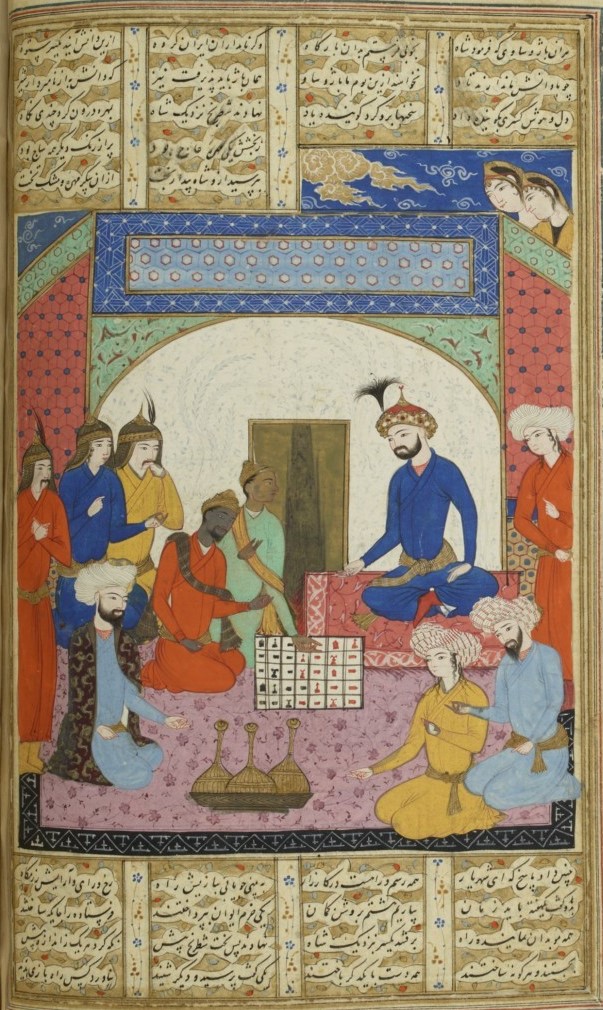

Scriptures from the early 7th century already mention chess. However, today we assume that chess was already known in the Persian region before that, in the 5th and 6th centuries. More recent archaeological finds support this. The Persian poet Firdawsi wrote the epic Shahnameh (The King’s Book) around the year 1010 AD. It contains a story from the reign of the Persian king Chosrau I. This story describes how the game of chess reached Persia from India in the 6th century. Whether India is indeed the cradle of chess seems increasingly unlikely, however, from today’s perspective. We know ancient chess pieces from this early period only from Persia.

Figural chess pieces already existed at that time. Some were found in excavations in Afrasiyab, the ancient Samarkand. Archaeologists dated these chess pieces to the 7th century. Such pieces were, however, the exception. Abstract chess pieces were far more common at the time. And they were made of all kinds of materials – stone, wood, jet, ivory, bone, alabaster, rock crystal, glass, ceramics and many others.

One of the largest collections of such antique chess pieces today is the Al-Sabah collection in Kuwait. But also many of the great museums of the world count antique chess pieces among their exhibits.

The way to Europe

From Persia, the game quickly spread to Europe. Archaeological finds of antique chess pieces show two routes of distribution. One is the northern route along the trade route of the ancient Silk Road, the other is the southern route via North Africa and Spain. Europe initially retained the abstract Islamic pieces. However, people gradually began to decorate them with figurative motifs.

Mid 12th century, Musée du Louvre, Paris, http://history.chess.free.fr/first-european.htm

In addition, Europeans developed their own figurative chess pieces, the most famous of which are the Lewis chess pieces. As art skills developed, more complex three-dimensional pieces were created. A new way of depicting the chess pieces also became established. In Persian chess sets, the pieces consisted of the shah (king), the vezir (the king’s advisor), the elephant (today’s bishop), the horse (knight) and the chariot (rook). This representation, which seems rather strange in Europe, was adapted to the existing hierarchy of the European courts. Instead of the vezir, the king was assisted by his queen, the elephant was replaced by the bishop and the chariot became more and more the tower of the domestic castles. Complex figural chess pieces were probably reserved at that time only for the nobility at the courts, where the game of chess is also likely to have been widespread.

The game changes

Around the second half of the 15th century, various changes were made to the game’s rules in Europe. These changes essentially concerned the movement options of the pieces. For example, the bishop, which until then could only move one square diagonally at a time, was now allowed to move as many squares as it liked along the diagonal it occupied. The queen, too, was given the now familiar completely free movement option and thus suddenly became the most important piece in the set. The result was that the whole game became more dynamic. Devastating attacks could already be made in the opening moves.

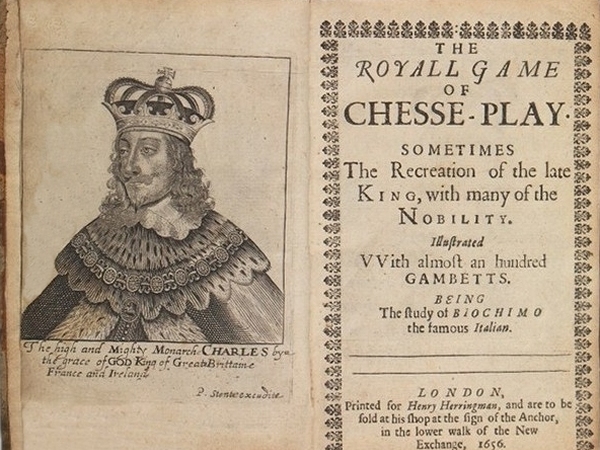

The first comprehensive publications followed, not only on the rules, but also on the combinational play and strategy of the game. Among the earliest and best-known of these books were “Libro de la invención liberal y arte de juego del axedrez”, written by Ruy López in 1561, and “Trattato del nobilissimo gioco de scacchi”, written by Gioachino Greco in 1620. Publications like these triggered an increasing interest in the game of chess, even though it could probably not yet be considered a popular sport at that time. Nevertheless, the game of chess was no longer confined to the courts of the nobility, but spread to the emerging middle class.

This development of the game again had an influence on the design of the pieces. Complex figural chess pieces served as a status symbol for the rich and for reasons of prestige. As it was the era of discovery voyages, there was also a first strong interest in chess pieces from foreign countries, especially India and Asia. Chess sets captured political and social events. Individual pieces resembled small works of art. However, these pieces were not suitable for serious play. They were difficult to transport when travelling. This was a problem especially for the merchants and patricians of the growing bourgeoisie. They required simpler, abstract pieces turned from wood.

The Transition to the Industrial Age

In the 17th and 18th centuries, woodworking techniques became increasingly sophisticated. Technical progress also found its way into the manufacture of chess pieces. New techniques and tools made it possible to create ever finer designs, e.g. through the development and increased use of ornamental lathes from the end of the 18th century. Around this time, the design features that we are still familiar with today became established. The highlighted size and a crown emphasized the special significance of the king and queen. In the case of the king, this was later often supplemented by a cross finial. The rooks were depicted as towers, the bishop was given an abstracted mitre and the knights were marked by horses’ heads.

The Industrial Revolution led to increased productivity and brought considerable prosperity to certain parts of the population. For these classes, leisure time took on a new significance. Games became more popular and were played in particular in coffee houses. Talented and professional chess players were active in some of these coffee houses, such as Philidor in the Café de la Régence in Paris.

At the beginning of the 19th century, chess clubs were formed in many cities in Europe. In these clubs, chess was not just a pastime. Rather, there was an increasing need to compete. Tournaments were organised. This encouraged the need for suitable tournament chess pieces. Chess sets were developed which enjoyed great popularity in individual clubs and after which they are still named today. These include, for example, the St. George style pieces (named after the St. George Chess Club in London) or the so-called Edinburgh Upright pieces (also Northern Upright, named after the Edinburgh Chess Club with which they are associated).

The golden age of chess piece making

From my personal point of view, this period, i.e. the late 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, was the golden age of chess piece making. A multitude of different patterns and styles competed with each other. The competition of designs led to true masterpieces of craftsmanship. The pieces were not only made of materials that were available in large quantities in Europe. Rather, exotic materials from the most diverse regions of the world were also increasingly used. For example, English chess pieces made by the country’s most famous woodturners were made in the finest African ivory or tropical woods such as rosewood and ebony.

The Europeans, especially the British people, imported chess pieces skillfully made by local craftsment from their colonies, in particular from India and China.

The development of the Staunton pieces

What all the pieces had in common, however, was that they were not yet fully suitable for tournament practice. Despite the symbolism that had already been created, many sets lacked the ability to distinguish between the pieces. This made the positions on the board confusing. Some of the pieces were poorly balanced and fell over easily. All this led to the development of the Staunton pieces in 1849, which are still in use today.

Of course, there are numerous variations within this pattern. But pieces of this type are ubiquitous today. Even though they revolutionised chess as a sport and potentially made it possible as a popular sport played by masses, they have not only enriched the chess world. Their success on the board and their aggressive marketing led to a veritable elimination of other types of pieces, which after 1849 had a niche existence at best. The advantages for the game are thus offset by a considerable loss of variety in the playing material.

The above description is nothing more than a very rough outline. Of course, there are numerous gaps and exceptions. Filling these and taking a closer look at individual periods, patterns and also materials will be the subject of future articles.

Daniel

Chuck Grau