Long time ago I was reading a book in which the author created a character who had an obsession for lists of top 5 of that particular thing in question, which could be the top 5 rock songs, or the top 5 sportmen, or top 5 movies etc. (Nick Hornby – High Fidelity, definitely the book to read after a breakup!)

I think we should do the same for each of the top chess players, we should know their top 5 or 10 games. Sometimes it can be interesting also for minor players, who have written extensively about chess.

Why?

Chess is more than just winning a game in a weekend tournament. There is definitely a lot of fun in playing competitively, and I love it. I love the preparation which goes for a tournament, the profiling of the players who are involved, checking my previous games in that same tournament, etc. But there is more to chess! Some love to collect chess clocks, some chess pieces and boards, and some enjoy the history of the game, or just play correspondence because OTB chess is too intense for them.

I’m always curious to see what one’s player consider his top games. Often we have games collections for world champions which are not made by the world champion, and we see a rehash of the same games over and over, but we don’t know what that player considered a triumph, a burning sad moment, or a disappointment which marked his career.

60 memorable games by Fischer is one of the most sold books in chess history.

In the introduction the author tells us how his selection was marked by his memory, thinking how good some games were, and how the engine damaged his selection and pleasant memories showing him how those games he loved were flawed!

Personally while I understand the need to use engines today to know the truth about a certain position, I also feel those games played 50-60 years ago, without engine assistance, were in a sense more real and artistic, because they gave a glimpse of the human spirit at work. While one can criticize a faulty analysis, could he really achieve the same analysis without an engine? Today we see too many amateurs switching on the engine, and thinking to know the truth about a position.

Let me make an example from one of my tournament games, we entered an endgame in which my opponent had the queen and I had the rook, against an engine I would resign because I know I would lose it. But against a human I put up the strongest fight I could, and the result was a draw because within 50 moves my opponent wasn’t able to win.

One thing I’m always curious about are previous books the author published with his games. Timman in the introduction mentions another book published by New in Chess: “Chess the adventurous way,” which featured 80 games from the period 1983-1994.

In the introduction to this new book Timman shows 5 games (2 complete and 3 fragments) which were not selected for the book, and explains the reasons. This book is made by 6 chapters.

Chapter One: the road to the top (1967-1977) Timman explains how he was endlessly traveling from one tournament to another, how the clock, in that time actually ticking, was the controller of a player’s emotions. Timman makes a comparison of how different is the path for a player to reach the world championship in his times compared to today.

In this chapter we also discover who were Timman’s role models: Botvinnik, Smyslov, Spassky and Fischer.

Timman mentions two good draws he made against Smyslov and Portisch, they are not in this chapter, so I took the liberty to find them and include them in this review to satisfy my curiosity:

Chapter one contains 17 games. Timman ( born in 1951) recalls when he achieved the International Master title, thanks to winning the Hoogovens Masters group in 1971,

This is obviously funny, because today if a prodigy is not a GM by 12, he wouldn’t be considered a possible talent and contender to the world title, but in that time, 50 years ago, to achieve the International Master title at 20 was considered a great achievement.

Timman recalls how other champions were developing faster than him, he mentions obviously Karpov (1951), and then continues with: Ljubojevic (1950), Ulf Anderssson, Ribli (1951) and Mecking (1952).

Timman became GM in 1974, this is obviously a very important step in his career, because gave him the chance to have more invitations to prestigious tournaments.

Chapter Two: the blockade (1978-1980)

In chapter one Timman begin to mention the theme of stability, and how important it was in achieving positive results. In this chapter he begins to mention again how to live a more disciplined and quieter life brought him to have more stable results.

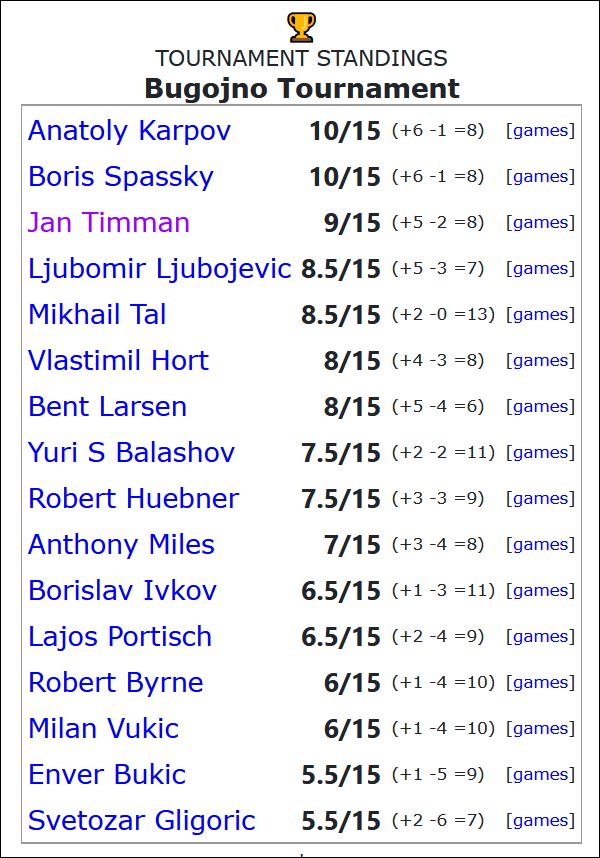

Timman considers a big success his third place in Bugojno 1978 behind Karpov and Spassky:

I’d like to share in this review the 15 games played in that event because there is more to a great player than just 100 selected triumphs, for example his win against Portisch is definitely brilliant and a game to study. Another win against Karpov then world champion must have been quite exciting, and made me think how everyone is always trying to win a world champion. Such game is well annotated in the book (game 18):

These 15 games also gave me an idea of Timman’s opening repertoire. I always ask myself if my openings are sharp enough, or if they are the one to blame for my results, but after watching Timman’s games I understood it’s a question of creativity, once going out of the opening phase. Sometimes also games which ends in a draw can give us an idea of how hard the two players fought. Another of the games given above which the reader can find strange is the one against Huebner, a top world player, who gets dismantled in 21 moves. This is another interesting point about human games, external factors can influence the quality of play.

Then Timman mentions a breakthrough when he achieved first prize with GM Gulko in Niksic 1978 tournament. Also in this case it’s important to see the games, to get a glimpse of who Timman was in that period:

I’ve noticed Timman uses 1.e4 or 1.d4 and also 1.c4 which means he had a huge opening repertoire.Another reasoning one can do is that players in Timman[‘s time were becoming more universal. More tournaments were played, often with the same top players, it was becoming necessary to surprise them, or bring them out of their opening preparation.

Many modern chess amateurs cannot really imagine what means to play an 11 or 15 rounds tournament, because normally today we don’t have those. But for a moment imagine the energy and endurance one must have to play such long tournament.

On the other hand, for the case of this tournament, Timman won 5 games and drew 6! The draws range from 14 to 39 moves, some are clearly not fought at all, maybe justifying the lack of sponsorship in chess, because when one goes to see a Tennis match, he will not see the two players agreeing to a tie after 30 minutes. This also makes the case for Blitz or rapid, where the players can still agree to short draws, but at least one has not wasted a day watching a game.

Game 19 Timman vs Ribli is fully annotated in the book. This game is important, because it shows the level of opening preparation top players had in the end of the 70ies. In this case to win the game, or unbalance the opponent, when playing against the Sicilian Najdorf, one had to remember at least the first 18 moves!

In this sense this book is a treasure mine, because Timman mentions move 18th Nxf6 was played first by Vitolinsh, and then by Timman himself, followed by Kasparov, Huebner, and Beliavsky. Chessbase Megabase 2021 allowed me to find the games played by these players in less than 1 minute.

After the moves: 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 a6 6. Bg5 e6 7. f4 Qb6 8. Qd2 Qxb2 9. Rb1 Qa3 10. f5 Nc6 11. fxe6 fxe6 12. Nxc6 bxc6 13. e5 dxe5 14. Bxf6 gxf6 15. Ne4 Be7 16. Be2 h5 17. Rb3 Qa4

How would you continue from here? Before Vitoshlin they would continue with 18.c4, instead Vitoshlin played 18.Nxf6!

Thanks to Chessbase Megabase 2021, I can share many games played by the players above mentioned, who have played this line.

All these games show the difference of interpretation between these great players, and how even Timman lost against such line as Black.

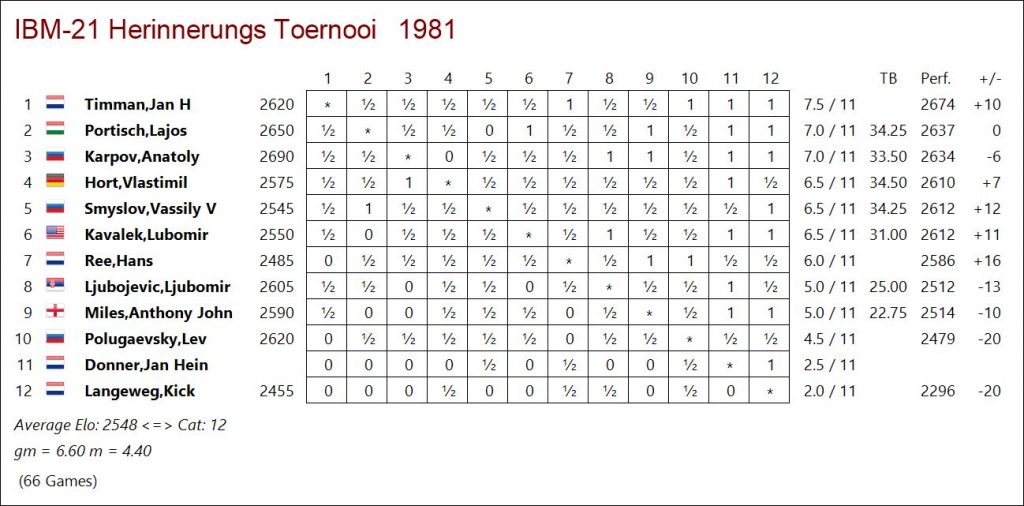

Winning the annual IBM tournament in 1978 established Timman in the top of the world.

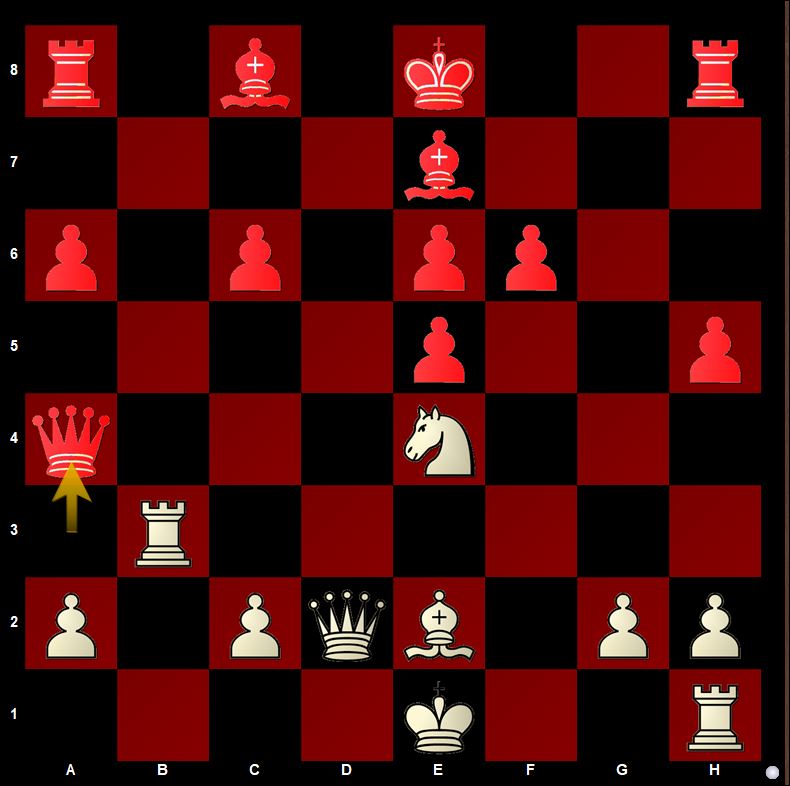

From the tournament’s standings one can notice the big names of that period are missing: Karpov, Korchnoi, Spassky etc. maybe there were political reasons (Korchnoi boycotted by the Soviet authorities), or they were playing in other tournaments, or preparing for world championship matches etc. While when the Soviets were playing, generally they were superior, like the Montreal tournament in 1979 showed:

In such tournament Timman was defeated twice by Karpov., If Timman had to face Karpov in a world match in that time, he would have probably been crushed, as we can see when Karpov with Black demolishes Timman in 31 moves!

The following are the games from IBM tournament:

In the book there is a game with Dzindzi fully annotated (game 20), but is not from the IBM tournament. The game from the IBM tournament is a draw in 11 moves. Yet the game chosen in the book is quite important, because Timman shows how a space advantage can be converted to win the game!

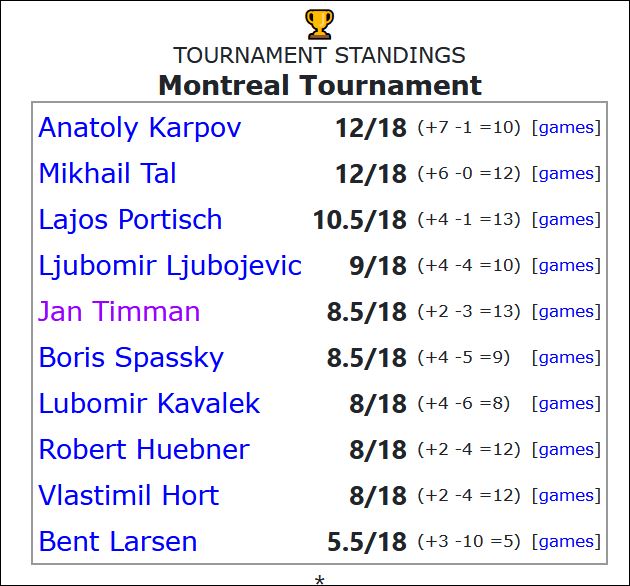

London 1980 wasn’t particularly successful for Timman (but for Nigel Short it must have been a nightmare 2 points out of 13 with 9 losses!! Yet, maybe this is the test all great players must pass through, and show how they don’t give up and continue to fight). In the book Timman annotates “an excellent technical” win against Browne, however from the same tournament I found the following miniature against Larsen!

Chapter Two has 15 well annotated games, the nice part is that each game has an introduction, with some anecdotes, and how some tournaments mentioned went.

Chapter Three: Best of the west (1981-1985)

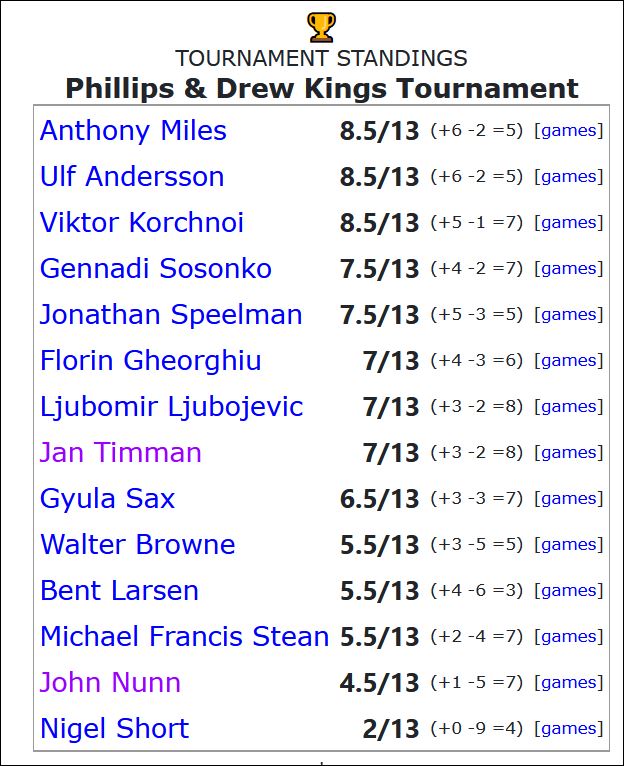

Here Timman recalls how he reached n. 2 in the world list, and another tournament victory which was important for him: Amsterdam 1981, ahead of Karpov.

IMAGE AMSTERDAM_1981_STANDINGS

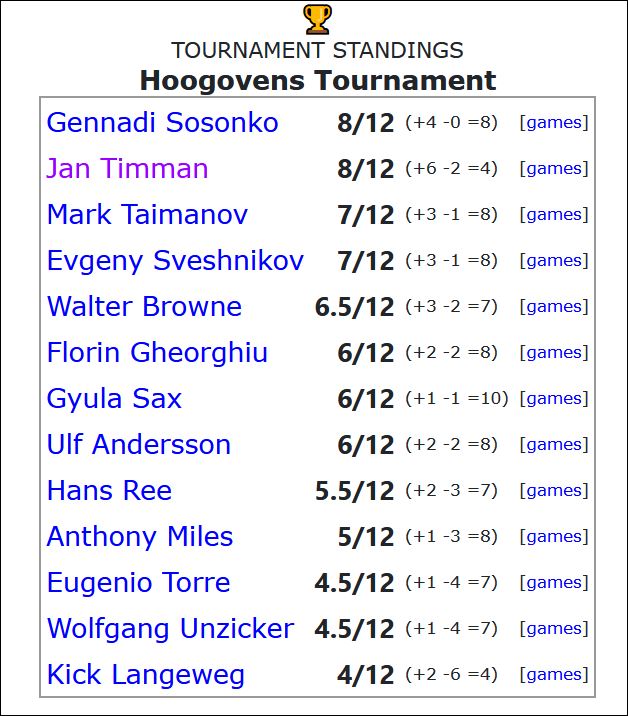

Another milestone for Timman was winning Wijk aan Zee, such tournament is called Hoogovens 1981, here the standings:

Game 34 and 36 in the book are against GM Torre and GM Andersson both well annotated, and describe the climate of the tournament in those critical moments. In the following games one must pay attention how the openings shift fluidly from one to another. In the game Miles vs Timman it begins as a Queen’s Indian, but by move 14 it has a similar pawn structure of the Classical Dutch.

While the book is about Timman’s triumphs, watching all the games played by Timman in the tournament gives a clear idea of how important endgames are, and especially rook and pawns endgames.

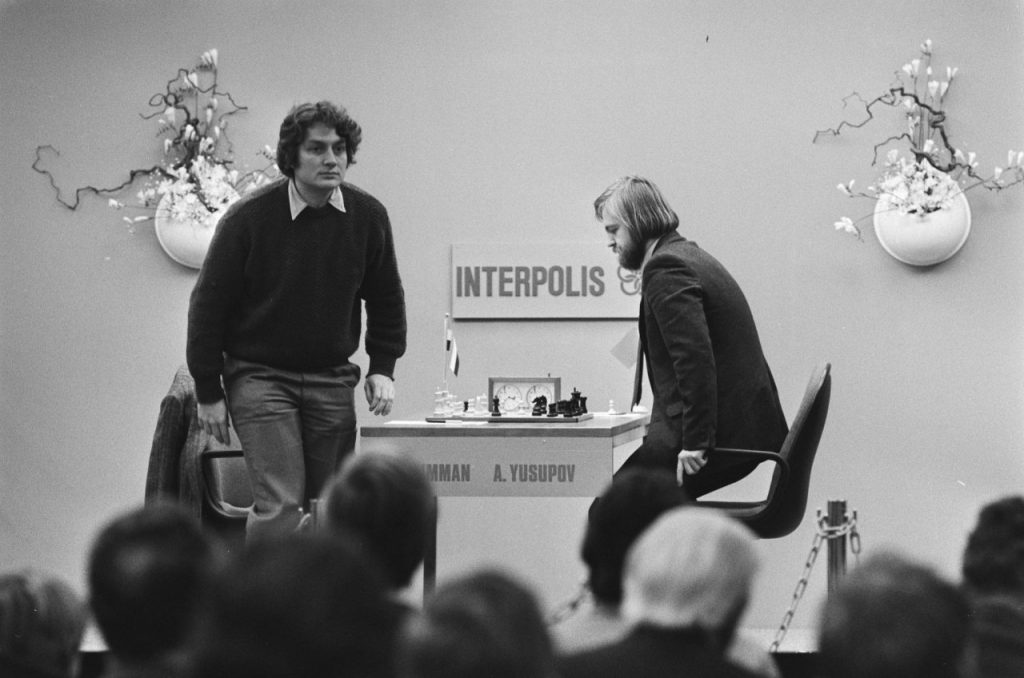

In this chapter he also mentions a very important thing, he failed the Interpolis tournament, in his words the cause was for sleeping problems, he began to suffer from Insomnia. I remember GM Dzindzichasvili also mentioned a similar problem when suffering decline in his tournament results, while on the road to the top. If this problem is common to top chess players, then there should be some solutions, maybe get some Melatonin in the evening?

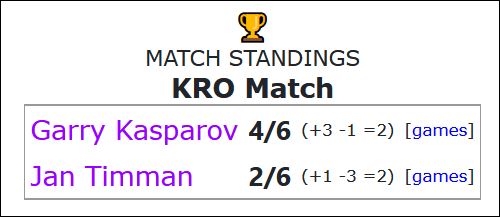

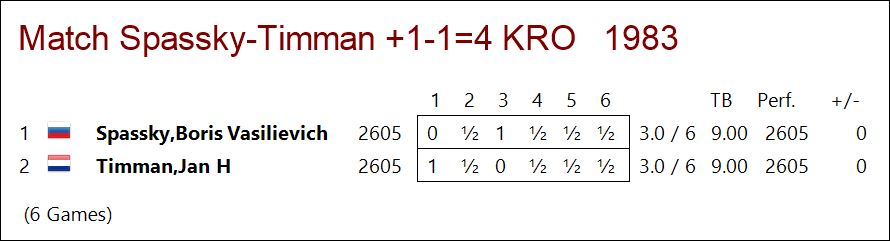

While searching the games of the match with Yusupov mentioned on chapter 4, I discovered, partly because Timman mentions it at page 145, which in Holland there was this broadcasting company KRO, which sponsored some of Timman’s matches against top players. In chapter 3 we find a game against Spassky, but Timman played a match also against Kasparov.

Such information is quite important, because Karpov with some bitterness mentioned he taught Kasparov to play chess, thanks to the long match which was interrupted. In fact Kasparov gained a lot of experience from such match, hence it should be true also for Timman, playing matches against Kasparov and Spassky was definitely an amazing training and learning opportunity.

While this is a book about Timman’s triumphs, I believe some games like the first of the match against Kasparov, are quite interesting and worth extensive analysis.

Game 43 in the book is the first game of the match played against Spassky.

While I understand Timman was flying all over the world, and participating in all possible tournaments, this match seems to show a lack of fighting spirit. Like for example the last game of the match drawn in 19 moves. The point here is: to become world champion, which is the aspiration or the dream of each top player like Timman, to achieve such goal one really needs to have a fighting spirit and will to win at all costs.

I found this chapter quite interesting, it was a wild ride. I felt the Man (Timman) suffering for his lack of consistency in results, and enjoying then 7 tournaments won in a row! The games selected in the book tell us many more anecdotes (like when he won a game against Tal, thanks to stay late at night talking with a poetess, and she gives him a powerful ointment…), personal thoughts (disagreements upon Karpov’s evaluation of some games, which were confirmed by engines), and discussion with other top chess players.

Chapter Four: the battle for the world title (1986-1993)

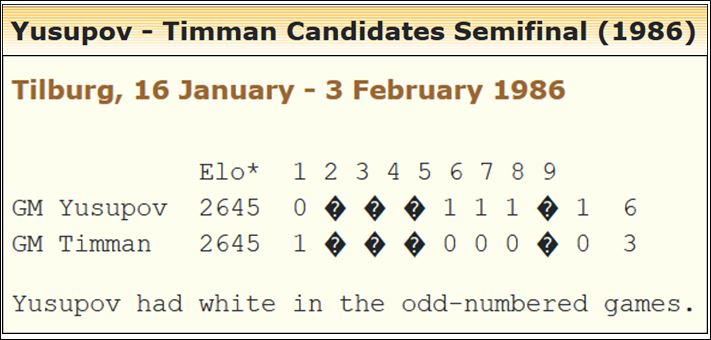

The chapter begins with Timman discussing his “old” age (34) for becoming a candidate, and how he lost a match against Jussupow.

Since I was not following chess back then, I went to check such match and relative games out of curiosity.

I found an interesting comment by Dvoretsky which described Timman. This shows how deep was the Soviets’ preparation toward western players.

“Timman has an active, fighting style, he is willing to go in for tense, confused positions. However, in so doing Timman often under-estimates the enemy threats and passes the boundaries of permissible risk. In tournaments of mixed make-up such a tactic usually brings him success, but in battles with leading grandmasters this trait becomes a weakness, perhaps the main one in Timman’s game. Jussupow was able to reveal it during the course of the match.”

Game 52 is fully annotated and the first game of the match, however I might have missed it, but Timman doesn’t explain why he lost the match so badly, and what he did to remedy such result in the future.

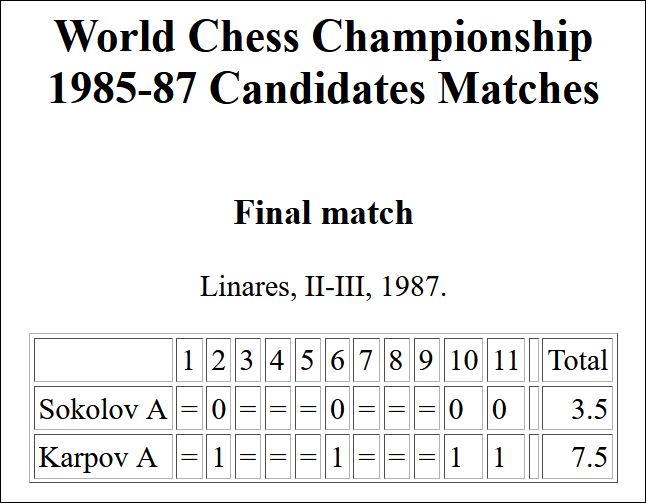

Clearly the result was brutal, but in the end the last of the matches to select the candidate to challenge Kasparov was between Karpov and Sokolov, and also in that case Karpov proved he was above and beyond the competition, pulverizing Sokolov:

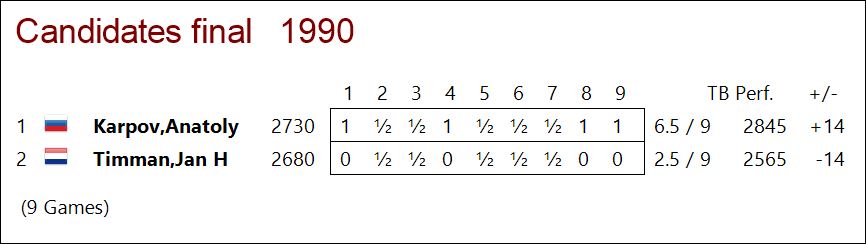

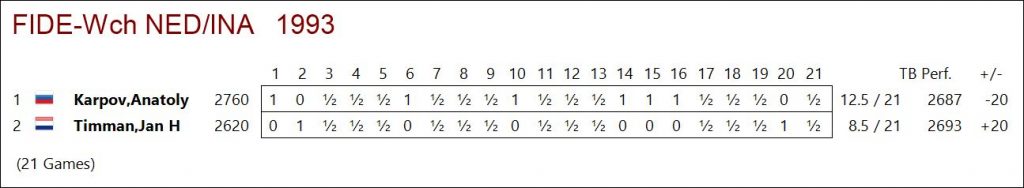

Keep in mind the above image, because we can see Karpov’s superiority also in the direct match versus Timman:

These are the games from the 1990 match, as we can see Karpov didn’t lose one single game. While researching the games of the match, I found the following quote from that period, which is quite funny, because it shows already in that time chess players had TMI (Too Much Information):

“<Timman lost the first game playing the White pieces in a way that didn’t receive any respect, especially after Filipino GM Eugenio Torre pointed out that the variation Timman played (he lost a pawn for nothing) had been previously analyzed by Karpov in New in Chess. Timman is the Editor-in-Chief of that magazine!>

Source: Inside Chess Magazine 1990 #10”

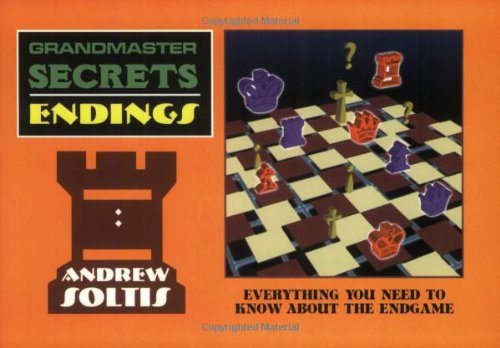

I found interesting to see these games, because the second of the match is analyzed in Soltis’ book: Gradmaster secrets endings

By game five, one can see Timman is grasping at whatever he can find to survive, and avoid to lose another game. Probably the same feeling Fischer’s opponents had in a match against him!

One question I would have been curious to ask to GM Timman would have been the following, based on the idea that in chess we can learn from the past (and maybe it’s just a myth): By 1990 Karpov and Kasparov had played 118 games in matches against each other. Would a deep knowledge of their games be of any help to win a match against Karpov? Or maybe Timman would never beat Karpov, because Karpov calculated a move or many moves farther than Timman?

Obviously we need also to take into account the teams behind the players, who found theoretical novelties for them.

The match is worth watching, also for some openings, for example to see how Timman fared against Karpov’s Caro-Kann. Spoiler alert: Timman got smashed!

Destiny gave another shot to Timman to win Karpov and show he was the best, but the result was like the one above, quite negative, showing Karpov was at another level compared to Timman.

Image FIDE_WCH_Karpov_Timman_1993

Often some of the games have stories, or ridiculous excuses, like game 7, Timman was late, because someone sent away his cab, and that explained his lack of fighting spirit. I guess there is a reason why some don’t become world champions… the fault is the taxi driver! LOL

But there are even more funny stories watching these games. For example Game 11 was drawn in 11 moves. The excuse this time was the funding of the match, here a short explanation:

“<It emerged during the Arnhem portion of the match that the Dutch organizers had only pledged 500.000 SFR toward the match, which was earmarked for expenses rather than for the prize fund. Oman also withdrew its offer to finance and organize the second half of the match.

FIDE had obviously failed to procure the bank guarantees which had always been its routine procedure in agreeing match sponsorship. It was not clear how much of the match arrangements had been a bluff on the part of Campomanes in reaction to the PCA match. Timman commented, ‘This is the first time I have ever played a 12-game match for free.”

Honestly I would have played a match for the world championship for free! Because the real prize is to be called World Champion if one wins. But obviously there are players of class like Fischer, Kasparov, or Carlsen who will always be paid, because everyone acknowledge their status.

However this match is interesting also in another aspect, the 12th game was played on September 25th, the next game was played on October 17th, Timman had nearly a month to recover, regroup, and find some opening weapons to beat Karpov. Instead I believe the opposite happened, Karpov’s team clearly used the month’s break to prepare the openings and definitely beat Timman!

These are the games from the 1993 match:

A game I found interesting is Game 54 played against Alonso Zapata, a GM I know, because he lives in Georgia.

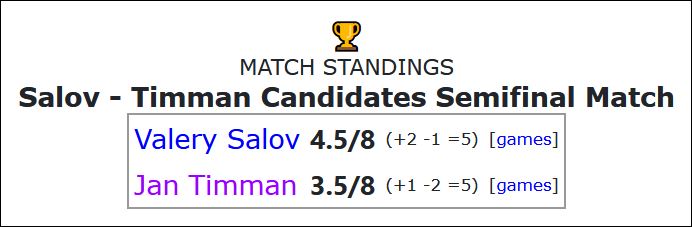

This chapter clearly details the climax of Timman’s career. It is possible to see he was never world champion material, but in the chess world there was definitely a gap between the top two: Karpov and Kasparov and the rest when playing a match. At the same time there is a court of characters which aspire to the top and then get rejected, the various Korchnoi, Portisch, Yusupov, Salov, Sokolov, Kamsky, Short, etc. I also found misleading the rating gained from tournaments, because in tournaments TImman was more lucky, and could win, depending on the results others had against the top. But when he faced the top in a match, he was clearly steamrolled! What I didn’t understand was why… for example did Karpov had a better opening repertoire than TImmna? Was able to calculate more? Kasparov is known to work on openings 12 hours a day, maybe that was the secret? In today’s world, with all our statistical knowledge, I think there should be this kind of information.

Chapter Five: the world title starts getting out of reach (1994-2000)

In this chapter Timman mention the choice a GM had to do in that period. Kasparov had created the Professional Chess Association, and being the real world champion attracted sponsors. Yet FIDE seems was not allowing GMs to play in both tournaments for the qualification to play against Kasparov for the world championship. Timman probably already knew by that point he wasn’t world champion material, and decided to stay with FIDE, also if that meant he would have to face Karpov, and the result was already known. Yet, time moves forward, and this time Timman found a more mature player: Salov, compared to the Salov he won 6 years earlier in a match, who defeated him on the road to the world championship, putting an end to Timman’s dreams.

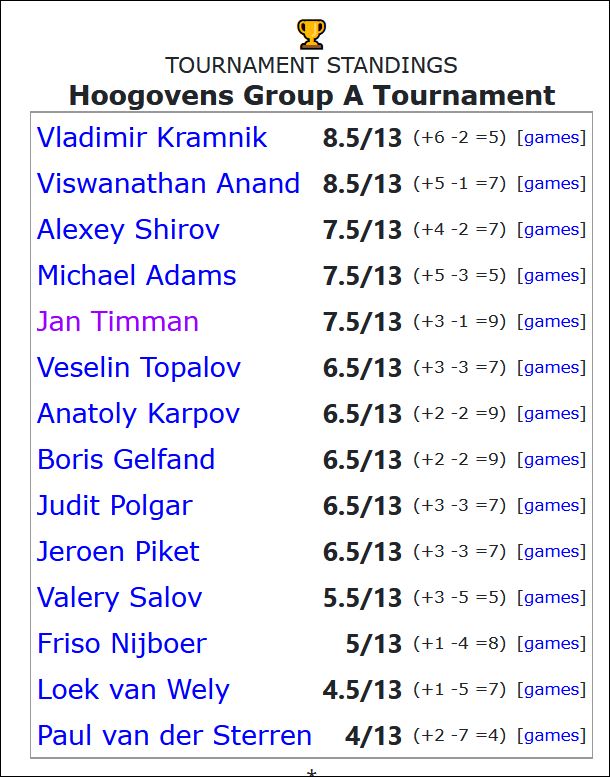

From this chapter we realize there are new young players entering the arena, and winning the tournaments once Timman was winning, the names are pretty famous: Kramnik and Anand.

And this is one of the criticism one could make to the book, the lack of standings. Timman says he arrived third in the Wijk an Zee 1998 tournament, but the standings tell us a whole different story.

Wijk_an_zee_1998_standings

We can see Anand and Kramnik dominated such tournament, and the top like Timman and Karpov are beginning to fade… in fact we see also other young players who are the new top of the world, their names quite famous are: Shirov, Adams, Judit Polgar, Gelfand, Topalov…

Chapter Six: in the New millennium (2001-2019)

Some older players instead of retiring begin to play rapid tournaments, because it’s the only way they can win, before the oxygen run out! In this chapter Timman described how he found more interesting working with computers.

Pro and Con: sometimes in books which are game biographies one would like to read more about the champion’s thoughts, and self-reflections. For example from chapter 2 we learned his important tournament successes were Niksic, Bugojno, and the IBM tournament. In the IBM tournament there is a draw against Hort in 11 moves. One would like to know if such fighting attitude or lack thereof, a draw in 11 moves, precluded him from actually become a world champion. Or what were the reasons behind such short draws (I found them in many other tournaments, even one against Tal in 15 moves, why wouldn’t Timman get the chance to play longer against such famous World Champion?). Let me also make a work analogy, how would my employer feel if they pay me for an entire day of work, 12 hours, and I go home after 15-20 minutes?

Or if a soccer team stops playing after 15 minutes and agree with the other team to a tie?

After reading this book one can wonder how Timman developed such universal opening repertoire (As White he played 1.e4, 1.d4, or 1.c4) and how he studied for it.

Maybe a lack of tables with the results of his important tournaments could be described as something negative and missing from the book. However today one can find such tables on some chess sites, and definitely on Megabase 2021 which has all of them.

I have included many in this review to give the reader a more complete view of Timman’s results.

One more serious criticism is the following, players at my level are able to follow games and lines without the use of a board. This is a good practice to keep one’s own visualization working. However one needs diagrams to start to visualize from that point. So the diagrams are of extreme importance, that’s why we buy chess books from top players, because they know when to put a diagram. Unfortunately also if this is a book precisely on Timma’s triumps, all the diagrams are oriented from White’s side, also when Timman is not White. I understand publishers will not make a million dollars more for orienting the diagrams from the correct side, but it would definitely improve chess books’ quality, and give a reason to buy a book, instead of having only electronic versions, or just taking out my Megabase 2021 and filter out Timman’s games. This last comment may be unclear to many not using the latest chess tools, but in Chessbase I can also filter games with medals for endgames, tactics etc. So to take out 100 of the best Timman’s games it would just take few clicks.

Final Thoughts: Definitely a book to have in one’s own library. Thanks to this book I became aware of many important tournaments, and their games. It seems the wheel of time is never stopping, strong players come and go, sometimes there is a power vacuum which waits to be filled, and in that inter-reign of some sort some players climb to the top. Often books like this one show why chess is a sport, since there is a clear decline with age. All in all a book I’m happy to have read, and reviewed. After the end of the book, I continued to ask myself questions like if memory and depth of analysis were the main differences between Karpov and Timman, and if one could make an experiment to assess such differences, and then predict whose players will reach the top, or even become world champion. Memory seems particularly important at top level for remembering the jungle of opening lines one must memorize.