Thanks to Daniel Vanheirzeele I had the chance to interview some of Thinkers Publishing top authors. Their kindness, professionalism, and sincerity in answering some simple questions gave as result a kaleidoscope of answers which puzzled me. They are all titled players, playing and being in the chess world for over 20 years, and yet they are so different in the interpretation of the game and the way to improve in chess. We like to believe there is always a right answer, that things are black or white, yet chess proves elusive, and every author gave a different recipe.

DN: Spider Man was bitten by a radioactive spider, Captain America was a secret army experiment in creating a super soldier, what is your super hero story which brought you to the chess world?

AC: My super hero story was told by my father. It was about some mysterious American who somehow magically won all his games when playing the best players in the world. There was a number 6 involved a couple of times, and I was born on the 6th, so I quickly figured out that I must become like him.

DN: Many would like to become titled players, but maybe they don’t understand the number of hours one needs studying chess and playing in tournaments weekly, do you have an estimate number?

AC: There is no number. It’s the total immersion that counts and only that will do. It’s the same with any professional endeavor, it’s not a surprise that only those who have started very early and have been engulfed by their calling reach the greatest heights.

DN: Tactics is mentioned as a weak point of the amateur or club player, yet the chess market is full of books about tactics, apps with thousand of tactical positions, and sites with tactical training. Maybe the real problem is the translation in the amateur brain between the 2D of the screen and the 3D of the chess board?

AC: Tactics is the weak points of all (human) players! I don’t think 2D and 3D matter so much, there were no screens not so long ago and yet the problem was the same. (I guess you can say the books were 2D back then!) If we go back to the immersion I mentioned above, the desired state is when the tactics is so well drilled in that it becomes second nature. And you realize it has become second nature when you see tactics without effort during a game, when it comes naturally and you just see it. And there is no shortcut to this state, but there is a guarantee that years of determined drilling will get you there.

DN: Is it possible that visualization becomes worse with aging?

AC: I don’t know about aging, but I do know that visualization does get worse with lack of practice. Unfortunately I’ve experienced this myself, though I know that a week of blindfold solving of exercises will get me back to a more or less acceptable level.

DN: What do you believe is the reason older players cannot keep up with younger players at GM level?

AC: The main reason is stamina. The younger players can more easily keep their concentration at a high level for longer periods and also in situations with high tension and pressure while older players tend to crack in such circumstances.

DN: Capablanca or Lasker were famous for answering the boring question: how many moves do you look ahead with an answer like: just one, the right one etc. Yet, watching many of Bronstein’s games it is possible to see he really calculated 4-5 moves ahead quite precisely, before launching an attack or approving a sacrifice, and that can be seen also by some time-stamps he wrote during the games. Do you think it’s normal in today’s chess world to calculate 4-5 moves ahead?

AC: Capablanca and Lasker were just playing to the crowd with those answers. In order to have control in a position, like all strong players aspire to, one must calculate at least 2-3 moves ahead against a relatively wide selection of opponent’s moves. This is very taxing, especially as the game progresses and everybody knows that the blunders most often happen on the first or second move of the variation. The best players are those who manage to avoid these blunders. They do it by keeping their concentration throughout the game, which allows them to calculate precisely and not miss things.

DN: Kasparov latest blitz tournament surprised everyone, because he had a 2300 performance. After the tournament he said that the evaluation of the openings he played, was totally changed by nowadays engines, compared to his former analysis and evaluations. It seems at professional level the real research is made by engines, not humans. What do you think about it?

AC: I remember an old (I think it was given after the match in London 2000) interview by Bareev where he said that it’s the computer that comes up with ideas, not the players! The computers are definitely doing most of the work and it is very rare that a human move that is not in the engine’s top 5 choices is a good one. Exceptions exists, but the “trick” in elite chess consists of analysing and playing the engine’s 3rd (or 4th) choice with the hope that the opponent had missed it. As for Kasparov, I think he overexaggerated the problems of his openings, his main problem was that he quickly lost the fighting spirit, was unable to regain it and then he collapsed.

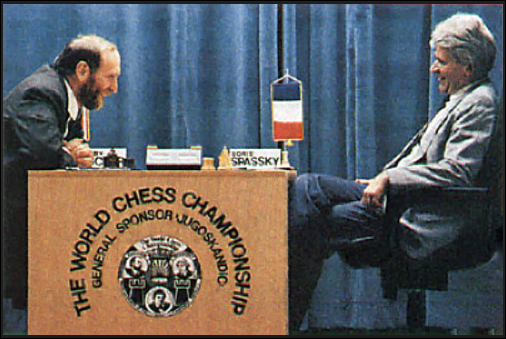

DN: Fischer was struggling in opening preparation for his 1992 return match against Spassky, once more it seems at professional level the opening phase is the most important part of the game, what do you think?

AC: Yes, for 2700+, definitely. The reason for this is that these guys won’t allow you to get away with a bad, or even inferior, opening. But below that level, and definitely at amateur level, the opening is never crucial. Even if you mess up big time, it’s quite probable that your opponent will give you a chance to come back at some stage, so the most important thing is to fight and look for chances.

DN: Can you play Blindfold games, and what is your opinion of blindfold play?

AC: Yes, I can. Blindfold play (or solving of exercises) is an excellent way to train visualization, which in turn makes it easier to calculate variations when playing OTB. It gives clarity to the lines you see in your head, thus lowering the chances of missing something important.

DN: I listened to an interview with Anna Muzichuk, and she kept her preparation for the women’s world championship secret. Does it really mean she does something all other modern professional players and their coaches don’t do and don’t know?

AC: At the highest levels people know how things should be done and they do them. Keeping one’s preparation secret is natural as nobody wants to give their opponent an advantage by revealing how and what they are working on. A case of a “preparation blunder” was the video from Caruana’s camp when preparing for Carlsen in 2018 when the laptop screen showed the names of the lines he was working on.

DN: Some titled players are paranoid about playing online because of cheating. What’s your take on it?

AC: I am one of them! I think that says a lot and I never play online. I know that FIDE, ECU and the platforms are working very hard on tackling this problem, but it’s a practically impossible problem to tackle.

DN: Titled players before Chessbase all grew up reading books, some had even only 1-2 books (those from Soviet Union) who read over and over. Yet today thanks to Chessbase Megabase with over 8 million games, one can find everything with few clicks. Do you think books are still needed to learn chess?

AC: Yes I do, even though not all players who rise to the top in the modern age follow this path. Nakamura didn’t know who Smyslov was and didn’t feel the need to study the games of the past champions because he wasn’t going to play them. And yet the World Champions are all, without exception, cultured chess players who have devoured hundreds of chess books and continue to read.

DN: Do you remember some of the chess books you read when you were young, which were quite important in your improvement as chess player?

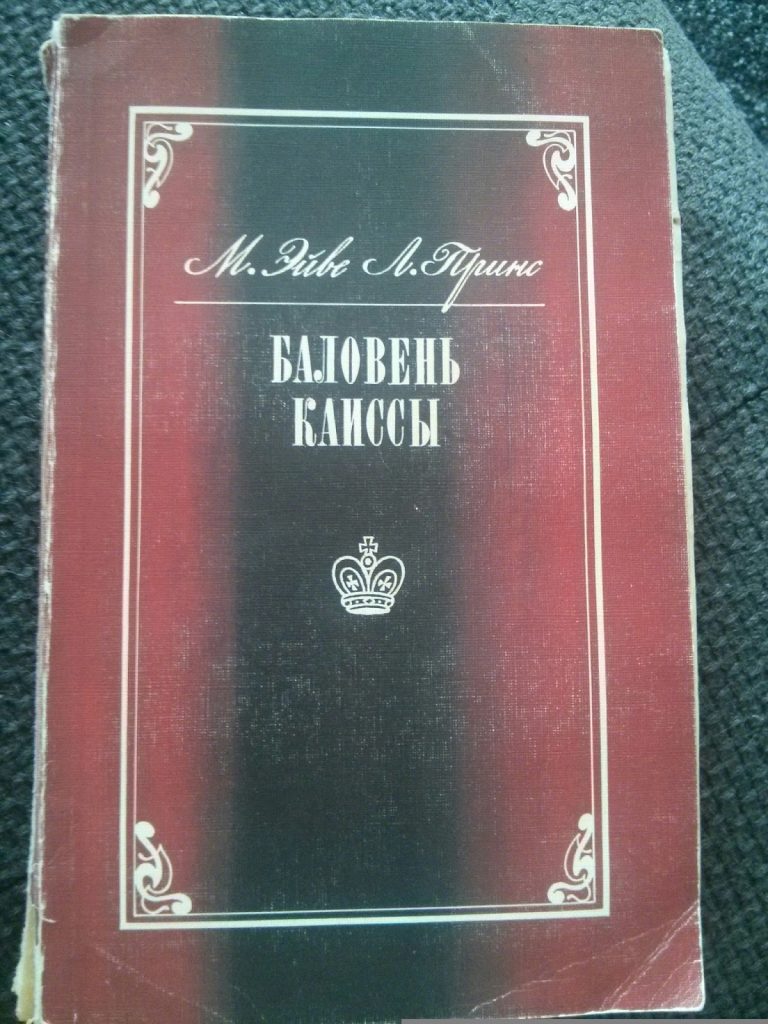

AC: I was given “classical education” by my father as he was reading to me the books of Nimzowitsch (My System), Kotov (Think Like a Grandmaster and Play Like a Grandmaster, these two were 1 volume in Russian, also his two volumes on Alekhine), Alekhine (New York 1924 and 1927, his game collections), Capablanca (everything he wrote), Botvinnik (the three volumes), Bronstein (Zurich 1953) etc. I made a qualitative jump in my chess understanding and playing strength after studying Capablanca’s games for 3 months straight. I used his books (My Chess Career, Chess Fundamentals, The Last Lectures) for his game analyses, Alekhine’s New York 1924 and 1927 and Kasparov’s volume on Capablanca, plus the extremely rare book by Euwe and Prins called “Baloven Kaissi” in Russian (to my knowledge no English translation exists – it translates roughly as Caissa’s Favourite). There were many others, of course, like Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games, Rowson’s books, Dvoretsky’s books, the Russian “black series” on many players (Rubinstein and Boleslavsky stood out for me), Kasparov’s books on his matches with Karpov etc.

DN: Reading some of Tal’s interview, he mentioned he would watch 70-80 games a day. Yet, when I try to watch some of Carlsen’s bullet games, I often lose myself in the analysis, or in asking myself why he didn’t play some other moves. Bottom line, when I watch 3-4 games a day, is a kind of record. Do you think is there a benefit in watching many games also if one doesn’t understand them?

AC: What I think Tal had in mind was more browsing than watching. I also remember reading that he would get a lot of chess magazines and would go over the games blindfold. It’s a normal work every professional does daily, quickly going over hundreds of games (for example every week when the TWIC comes out) in order not to miss an important opening development. When it comes to watching online, it’s difficult to understand what was going on even for stronger players, especially if the game goes on at high speed. In order to properly understand a game of chess more serious analysis is required and this takes time and effort. I think watching online chess is more entertainment than education, so in such case even not understanding something is not a big deal.

DN: Do you have any advice for senior players in the 2000 range who want to reach the master title (2200)?

AC: I am not too original when it comes to chess improvement and I touched upon this matter above – it’s all about tactics. If you don’t blunder and you take advantage of your opponent’s blunders you will be invincible. Now you know what you need to do.

DN: In the past century some top players said studying blitz games was stupid. Yet I’ve seen many of Carlsen’s bullet games on Lichess and he plays like an engine (at the moment his bullet rating is around 3150 like a weak stockfish), even some seemingly common moves he makes in the endgame have a plan behind it. The funny thing is: he using only 60 seconds for an entire game. What’s your opinion about it?

AC: I remember reading what Petrosian said to young Boris Gelfand. He told him that strong players always have an idea when making a move. Even with a few seconds on the clock strong players are able to see at least one move ahead, they are never guessing or playing a random move. With the practice the players are able to get thanks to modern technology, it’s not surprising that the best players can play so well with so little time on the clock.

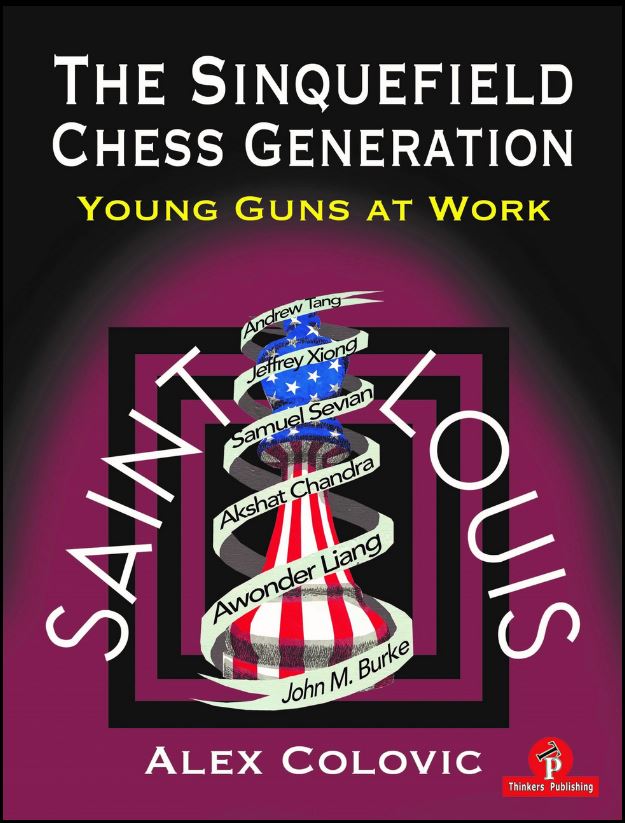

DN: would you tell us something about your book published with Thinkers Publishing ?

AC: I wanted to write a book that I would be very happy to read myself! I was fascinated by Botvinnik’s analysis of the styles of his opponents, when he would pick up characteristic moments from their games and note their repetitiveness, thus forming an opinion of their preferences. He would go over many games of his opponents and draw up their profile as chess players, which would enable him not only to understand them better, but also to predict their behaviour and reactions in practical play. Now, this was great to read about Tal, Bronstein and even Fischer, but why nobody did this kind of work for the modern players? Perhaps this type of work waited for me? And what could be more appropriate than analysing the styles of the players born in this century, you don’t get more modern than that. Add to this the American chess revolution, when thanks to the continuously generous help by Rex and Jeanne Sinquefield America produced a crop of exquisite talents, and you see how The Sinquefield Chess Generation came into being. It was very exciting for me to analyse the styles of Xiong, Sevian, Liang, to name but a few, and see how the 21st century players play chess, having grown up under the constant tutelage of the mighty engine. I was also lucky with this book because after I wrote it for several months it was in a limbo, due to various reasons, but then thanks to my friends from American Chess Magazine I got in touch with Thinkers Publishing and from then on everything went smoothly. I have always been certain that I would never write a book, understanding how much hard work it required, and yet here I am talking about my first one. And I cannot be happier for it!

DN: This concludes the interview, a Big Thank you to GM Colovic and Thinkers Publishing. If the reader wants to see other questions answered, please contact me on Facebook or Twitter