Few years back Jan Timman, one of the top 10 chess players in that time, published a book entitled: “the art of analysis.”

Today we believe to know the truth about a position thanks to engines. But if engines were switched off, how would we evaluate a position? In fact Caruana, another top 10 player, warned us of engines becoming a crutch.

Personally I tried to read the Informant, I even bought few issues, but everytime I read a game and their evaluations, often I cannot understand why that evaluation was given. And sometimes when I switch the engine on, even more question arise, because the engine’s evaluation differs.

This happened to me also while reading a Chinese Chess (from now on called with its original name: XiangQi) book.

The goal of this article is not to blame those who write XiangQi books, or chess books. The goal of this article is to show how hard is the journey of a XiangQi (or chess) player toward the understanding of the game, in view of recent advancement in technology, like the new NNUE engines, or even what could make a big difference in the achievement level between different players: visualization or calculation depth.

Once more I’m not here to make good or bad advertisement to anyone, so I will take a position from a book, and show how puzzled I was, and how puzzled every reader should be, because when we read a xiangqi book we need to ask ourselves some questions, and the fight to find an answer to those questions is what will make us better players. If instead we believe everything should be spoon fed to us, and we must not struggle, then we will be in for a tough wake up call when going to play a tournament.

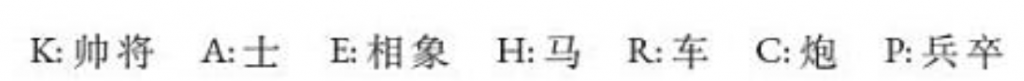

Here how to read the notation:

K=King, A=Advisor E=Elephant H=Horse R=Rook C=Cannon P=Pawn

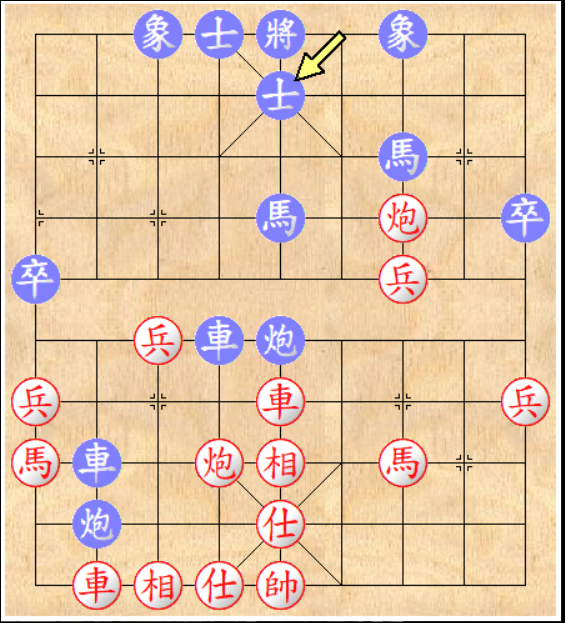

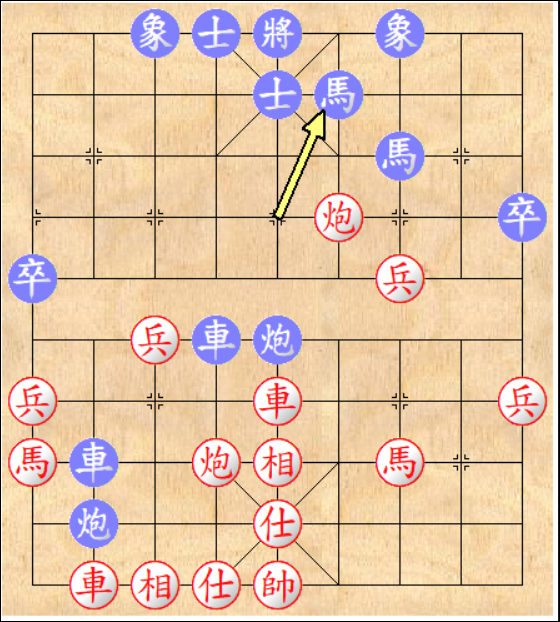

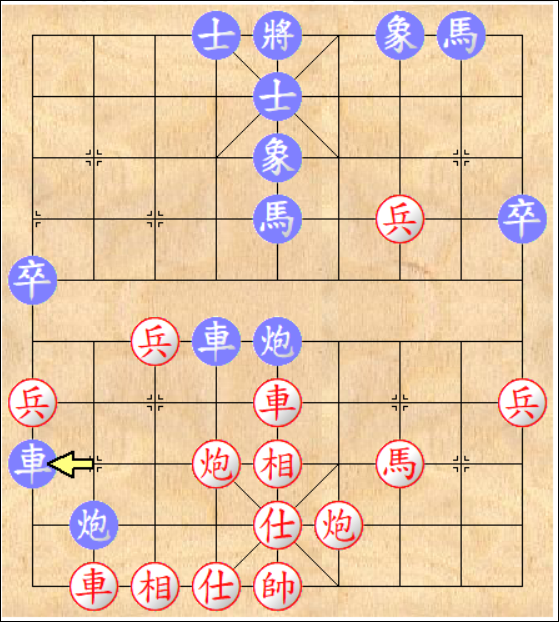

In the book where I took this game was written the following comment (translated from Italian, all mistakes are mine): “Very strong and interesting would have been the following continuation: 17.C3=4 with the idea C4-5! For example:

17.C3=4 H5-6 (this move is a problem for me, because I don’t understand it, and this is why I wrote this article)

18 C4-5 R2=1 19.C4=8 R1=2 20.C8=7

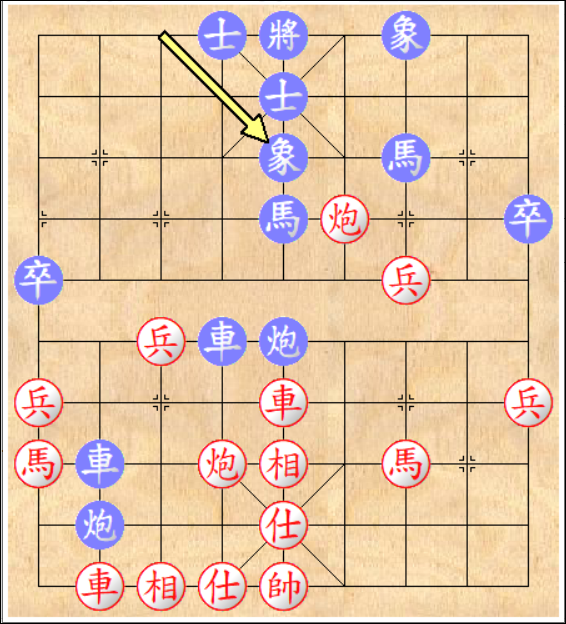

(This was another point which puzzled me, because if Red is able to do this kind of move which attacks and threatens checkmate playing C7+8, then I asked myself: why Black played H5-6, instead of playing a more meaningful move like E7+5 or E3+5?)

the book continued with: R2=3 21.C7=6 now Black has many possible moves but all losing. (the losing part is related to the rook defending the central cannon, which is attacked by Red, and how all these pieces are hanging once the rook moves or falls.)

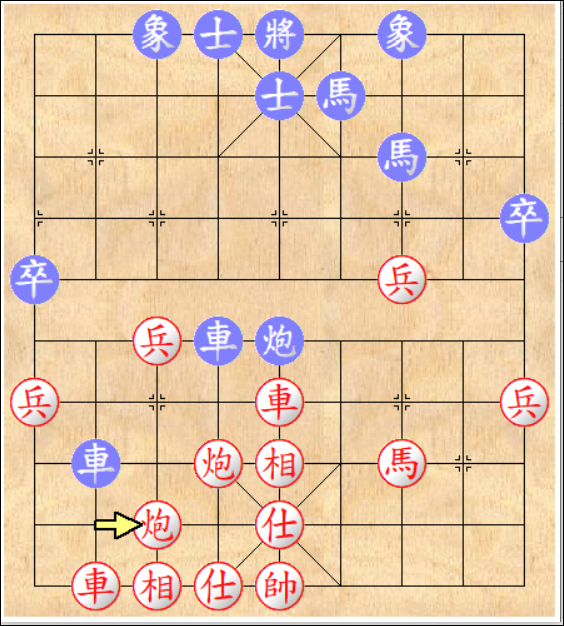

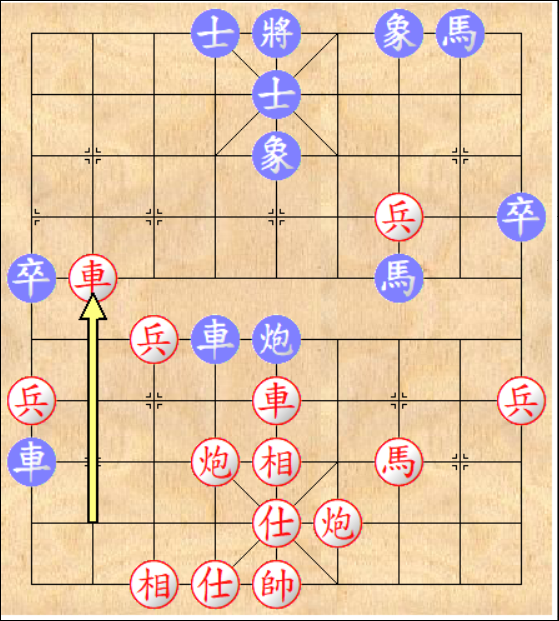

Let’s return to the beginning of the variation, and see why Black couldn’t play an elephant move. (let’s remember at this point the engine, Fairy Stockfish, gives a +7.56 to red as advantage)

17. C3=4 E3+5

This move takes away the threat of C4-5 and then once played C4=8 the next C8=7 doesn’t threaten to take the elephant and checkmate.

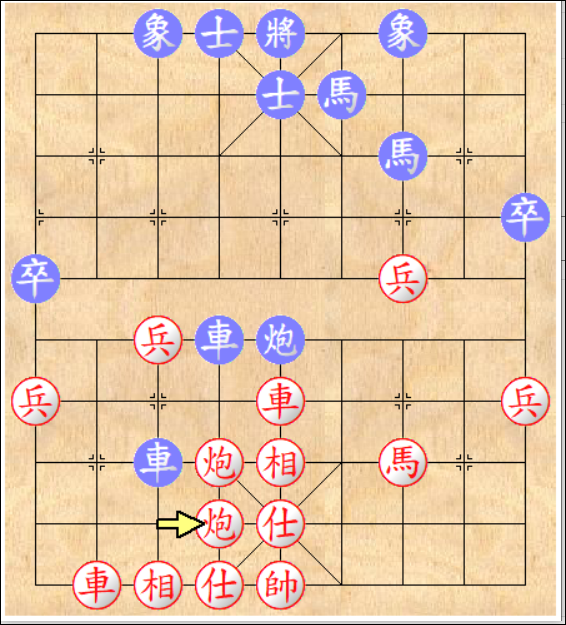

Fairy Stockfish (abbreviated as FS from now on) would play 18.P3+1 H7-8 19.C4-5 R2=1

The engine wants to continue with: 20.R8+1 because there is not anymore the checkmate threat, and consequently cannot deal the blow to the enemy rook defending the central cannon. 20…H5+7 21.R8+4 and now the engine, FS, is giving +8 to red, but can someone actually see what is the material advantage? Would someone of beginner level be able to visualize a 5 moves variation as should be done in a tournament game, and justify this +8 evaluation?

Is the Black rook really trapped?

Time to go to work, so I cannot continue the analysis. But I hope it was interesting. If one wants to see more exciting xiangqi games and lose himself in discovering why or why not some moves are good or bad, please buy the book, it’s in Italian, but I hope soon there will be an English translation.