I found this painting and it’s theme of “dominant women” so fascinating I wanted to elaborate on my process as well as the painting itself.

Josef Danhauser whose 40 years of life were all in the first half of the 19th century, was from Austria.

He lived during what’s called the Biedermeier period, a sort of un-adventuristic time that promoted the bourgeois life. Josef, with his brothers, inherited their family’s furniture-making business (which employed up to 100 workers) and Josef is credited with many furniture pieces from that time. He also became a very technically skilled oil painter, although he’s been criticized for being too pedantic and moralistic as well as staging his scenes as if they were a stage production. That actually makes sense since, as I read in the 1997 book, “Schubert’s Vienna” by Raymond Erickson:

“The master of the theatrical-literary genre of this period was Josef Danhauser, who worked for many years as a theater painter and married a singer who became a prima donna at the court opera.” His wife was Klara Josephine Streit, the daughter of a Viennese physician. Danhauser was acquainted with many famous musicians of the time such as Franz Schubert, Franz Liszt, and Ludwig van Beethoven. If fact, he and another artist, Matthias Ranftl, molded Beethoven’s death mask when he died in 1827. A short time ago I came across a painting by Danhauser that involves a chess game. In doing my usual cursory investigation into the painting I found the following interpretation cut-and-pasted on nearly every page that offered one: “The painting may depict a real event – a chess match between a banker named Escales and a Hungarian noble woman. They played because the lover of the noble woman had a big debt to this banker and that was the way she could gain back the debts – which she managed to do.” I was curious about this story, since I’ve collected similar anecdotal tales over the years but this one was new to me. I tried to research the story from one direction–the name of the banker. I did find a Baron d’Escales of Vienna who lived during the 18th century but no such stories about him. So, I decided to take a different approach and search out books from both that time period and later that critiqued Danhauser and his works. One book was very helpful. It suggested that the painting is a scene from Goethe’s play, “Götz von Berlichingen”

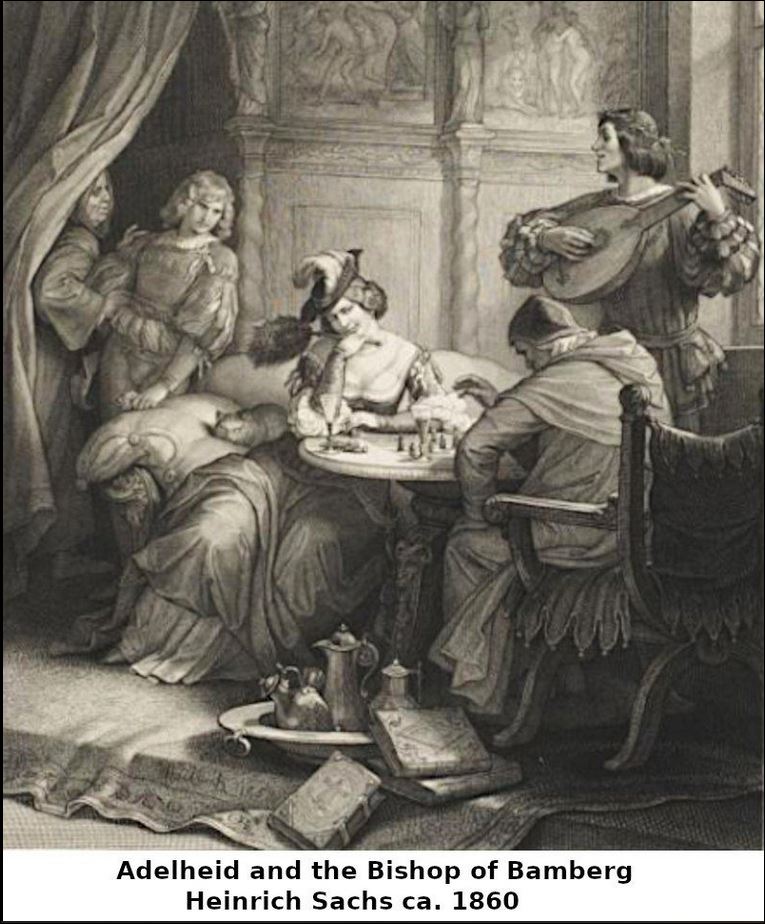

during which Adelheid plays a game of chess with the Bishop of Bamberg. Adelheid, a fascinating and unscrupulous beauty, plots the destruction of Götz through his friend Adelbert von Weislingen. The heroine, if that’s what she is, engages in a game of chess with the Bishop of Bamberg. While the old bishop is apparently absorbed in the game, Liebtraut, the minstrel, is playing on the lute and singing. (see the included 1860 sketch by Heinrich Sachs)

Adelheid to the Bishop: Your thoughts are not in your game. (Check to the king!)

Bishop Bamberg: There is still a way to escape.

Adelheid: You will not be able to hold out long. (Check to the king!)

Liebtraut: Were I a great prince, I would not play this game, and would forbid it at court and throughout the whole land.

Adelheid: ‘Tis indeed a touchstone of the intellect. (Checkmate!)

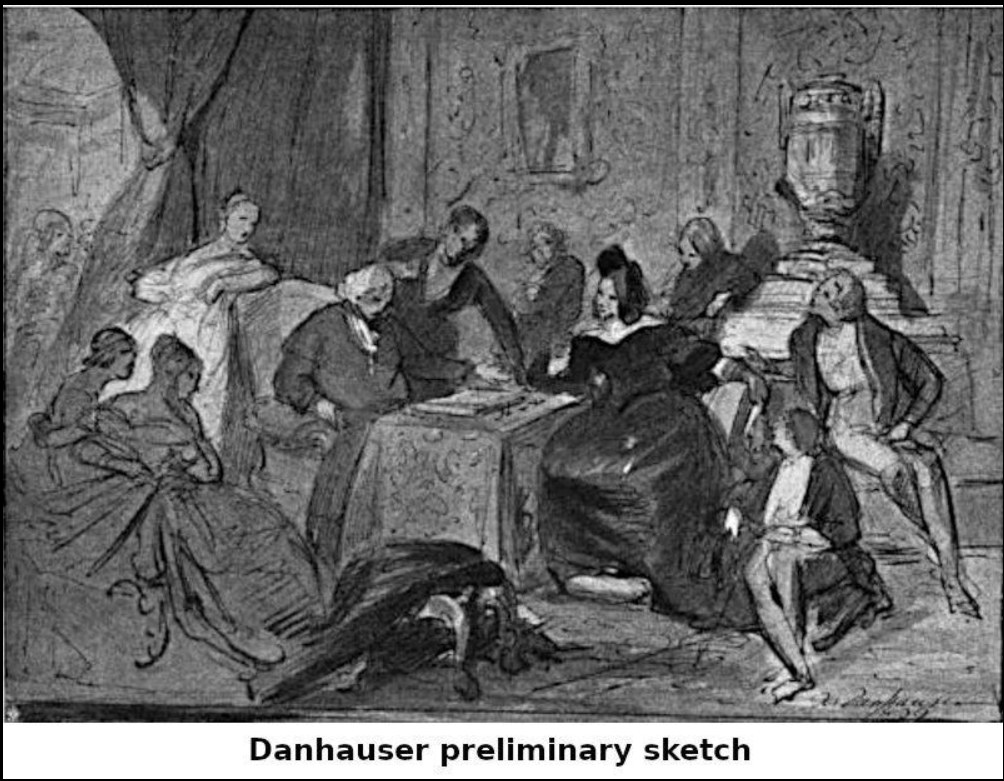

Given Danhauser’s theatrical background, and absolutely no substance to the banker story, this idea makes complete sense to me. But let’s look at the painting and preliminary sketch Danhauser drew.

One thing that’s most noticeable is that the painting is numerically dominated by women, just as a woman dominated the game. The statue in the top right is of Omphale and Heracles, a rather curious inclusion given the erotic implications usually attached to this mythological tale.

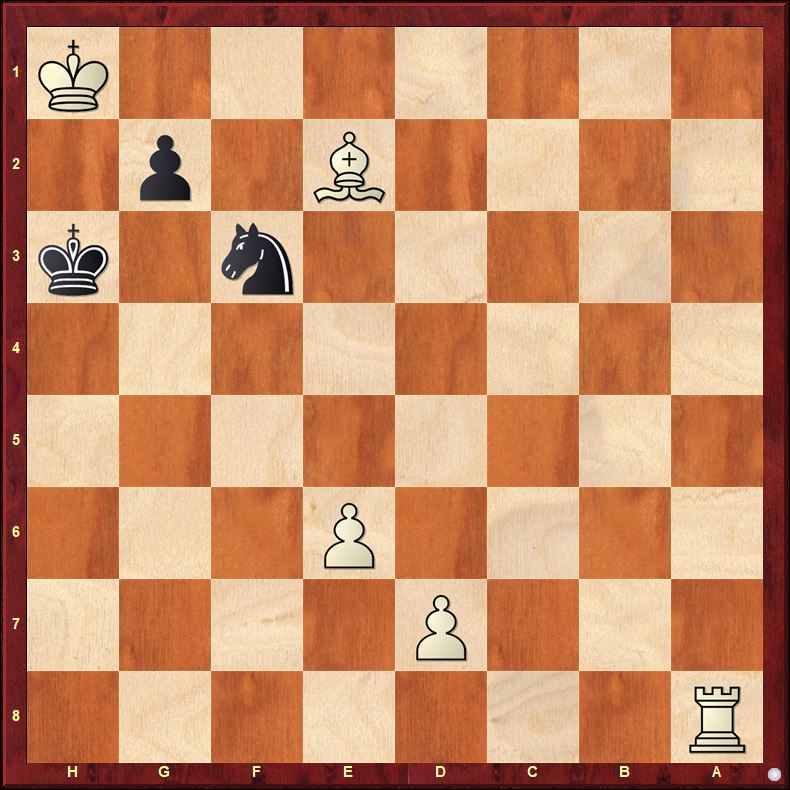

But it actually fits in nicely with the theme of dominant women, since Heracles was sentenced to a year of servitude under Omphale and in some versions was forced to do traditional women’s work while wearing women’s clothing, further humiliating him. In the painting’s chess game, Black (the woman) has just played g2# …(FEN: R7/3P4/4P3/8/8/5n1k/4B1p1/7K w – – 0 1) …which not only mates the older man but does so in a most demeaning fashion, particularly since he has the vast material advantage of R+B+2p to her N+p. At least she didn’t make him wear a dress.

Lat thoughts: While this painting seems most likely to have been based on Goethe’s play, it doesn’t try to replicate it other than in spirit. The man sitting down greatly resembles Liszt but for many reasons it would seem highly unlikely that it’s him, just as the other characters appear not to be known personages. This scene is, however, staged in Vienna.

This article is based on a Facebook post by Sarah Beth Cohen, famous chess writer, especially known for her painstaking historical research.