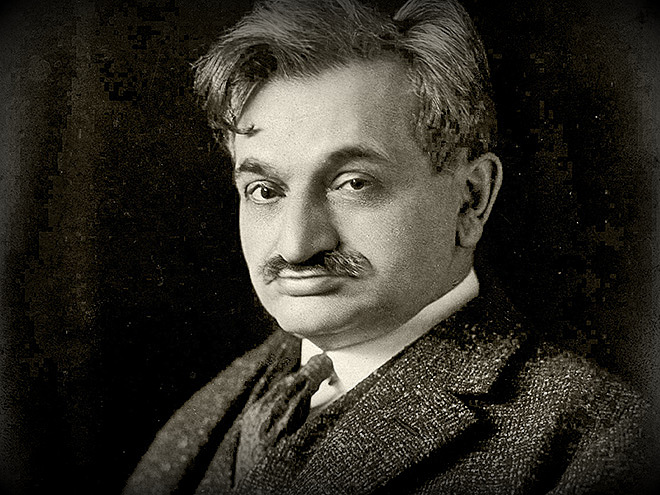

Rubinstein, like Pillsbury before him, was a player who may have been world champion if only he

had a shot at the title. In 1912, I believe he was the strongest player in the world.

Contrary to popular opinion, a dove’s world is not more mundane than a hawk’s. It is merely more subtle. Rubinstein’s strategic play and especially his endgame technique were unmatched for his pre-Capablanca era. In this game we look at his victory over Frank Marshall at San Sebastian,1912.

When a student asks me how to improve in endings, I always reply with the advice:

“Study Rubinstein’s and Capablanca’s endgames.” Rubinstein’s Style Which force is greater: that which tears apart, or that which binds?

To the great squeezer Akiba Rubinstein’s opponents, the words “endgame” and “strategic position” were synonymous with misfortune.

The Cause of Rubinstein’s Power:

Rubinstein was the greatest endgame player of his time, before the arrival

of Capablanca. Rubinstein was the strongest strategist of his era. Nobody,

including Lasker or Tarrasch could outplay him strategically.

Capablanca usurped Rubinstein’s natural right to challenge Emanuel Lasker by winning the

super tournament of 1911.

Rubinstein came back strong in 1912 by winning the same tournament, perhaps to prove that he was just as worthy as Capa to challenge Lasker. This game is from the 1912 event. Rubinstein was a precision instrument, not a blunt force object. Most myths have at least a partial basis in reality. Rubinstein didn’t play the endgame perfectly, but to his contemporaries and rivals, it certainly looked as if he did. The best way to describe his style is as if a cold, marble statue in a museum suddenly drew breath and came to life. His play is cold, yet simultaneously alive with both beauty and precision. Rubinstein was also clearly the strongest strategist of his era. If only Lasker had granted him a match around 1912, what a battle it would have been, between trickery and a search for truth.